Compared with her incredible achievements, her hair might seem minor. Here's why it matters.

Ida B. Wells Was an Reporter, Activist, and Leader. She Also Had Great Hair

Over one hundred years ago, Ida B. Wells became one of the leaders in the fight for women’s suffrage. In 1913 she founded the Alpha Suffrage Club, the first all-Black suffrage club in the state of Illinois. It was influential in the 1914 election of Oscar De Priest as the first Black alderman in Chicago. Shortly after forming the club, Wells traveled to Washington, D.C., to participate in the famed suffrage parade that March; as a Black woman, she’d been told to stand in the back—a request she defied. Wells inserted herself front and center, walking with the Illinois delegation. That’s a story you might know. What’s less appreciated is that she did it wearing her natural hair.

I have been thinking about Wells a lot over these past few months. On January 20, I watched Kamala Harris be sworn in as vice president of the United States. Like millions of other women of color, I was thrilled to see the historical significance of Harris as a “first” realized. But I also felt a unique tug. Because Wells, who had spent almost all of her adult life fighting for this moment to be possible, was my great-grandmother. She died 90 years before it happened.

The fact of Wells’s hair all those decades ago might not seem remarkable, especially in the context of just how much she achieved and fought for. But even now—no matter what Black women accomplish—our looks and hair continue to be subject to policy debates, legal battles, dress codes, political interpretations, and ideas about what is considered professional or not. In addition to having our work held up to different standards than our white counterparts, Black women have to endure a higher level of personal scrutiny in professional settings. We have had to navigate a racialized beauty hierarchy that prioritizes European features as ideal.

Wells fought against white supremacy, domestic terrorism, segregation, and educational and economic inequality. And she did so while wearing her hair in its natural state. She kept her chin up and her hair styled, often adorned with pins, barrettes, and beautiful combs.

As an orphan and later a single woman, Wells navigated physical dangers while refusing to shrink herself in a world that criminalized blackness. Compared with her historic achievements as an investigative journalist and activist, her hair might seem like a minor point, but it was in fact a quiet, constant public statement: She took pride in her appearance. Black women’s natural hair can be straight, wavy, curly, coily, or what some call kinky. It can range in color from sandy blond to jet-black. It can grow almost to our waists or be cropped close to our heads. Our thick natural hair can be formed into cornrows, box braids, micro braids, afros, pixie cuts, bobs, twists, locs, twist-outs, and buzz cuts. Black women use shampoos, conditioners, hair oil, hair lotion, vitamin oils, detanglers, curlers, rods, beads, clips, hairpins, and more. We’ve spun our hair into every style imaginable, including some truly gravity-defying geometric designs.

Wells’s commitment to wearing her hair in its natural state is just one more aspect of her legacy that connects her to some of the Black women blazing trails now. The activism of Stacey Abrams, who wears her hair in twists, helped pave the way for political victory in Georgia. Rather than shrink into obscurity after her contested defeat for governor in 2018, she created organizations that empowered the Black electorate. Her efforts contributed to the ultimate Democratic control of the U.S. Senate with the elections of Reverend Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff.

At the inauguration, millions of people were introduced to 2017 national youth poet laureate Amanda Gorman—a 22-year-old woman with a powerful message woven into her poem “The Hill We Climb.” Gorman’s poem paid homage to the sacrifice and dignity of enslaved people and their descendants who built this country. She also made a splash with her natural hair, which she wore braided, styled with a headband, and adorned with gold crimps. Gorman spoke both verbally and visually with pride and power. On Twitter, she emphasized the intention behind the hairdo: “I highly suggest a headband crown for anyone wanting to stand taller, straighter, & prouder.”

AdvertisementBlack women in power—from Washington to Hollywood—showcase the diversity and beauty of our hair. Some of these fierce women wear braids and locs like film producer and director Ava DuVernay and Sherrilyn Ifill, who is the leader of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund. Others sport afros or closer-cropped styles like those of Marcia Fudge, the Biden administration’s nominee to be secretary of housing and urban development, and Symone Sanders, chief spokeswoman for Vice President Harris. In Congress, Representative Lauren Underwood rocks her curls, and when Rep. Cori Bush delivered her acceptance speech, she was wearing braids. In fact, all three of the Black Lives Matter founders—Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi—have worn natural hairstyles in the past. Carrying a fierce message of hope and inspiration, these women are making statements about self-love in more than one way.

Black women—with their natural curly, kinky, coily hair—have made their way into positions of power, despite odds stacked against them. Generations of Black women, including my great-grandmother Ida B. Wells, have resisted the expectation and demands that they abandon who they are in order to fit into someone else’s standards. Their hair is one manifestation of that. There are so many more. They have been defiant in their self-pride and embraced themselves. And that alone is an achievement.

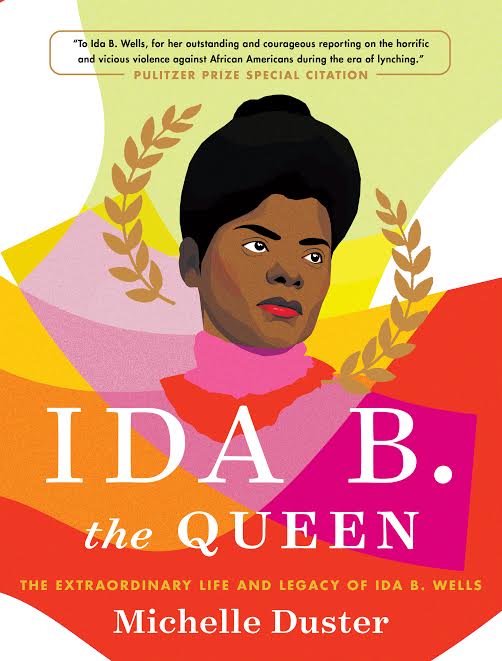

Michelle Duster is an educator, public historian, and author of several books, including Ida B. the Queen: The Extraordinary Life and Legacy of Ida B. Wells.

This story originally appeared on: Glamour - Author:Michelle Duster