"I needed these stories told."

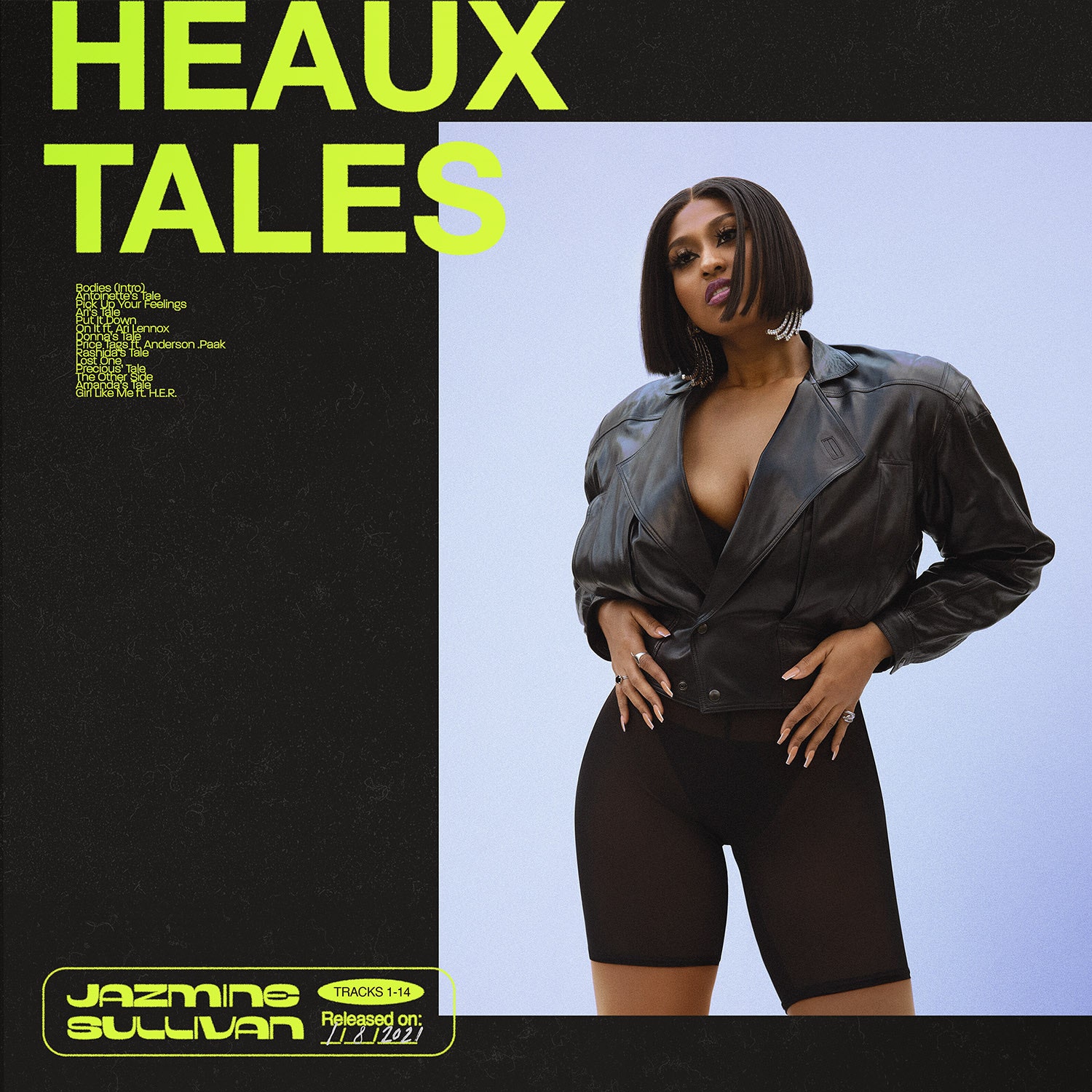

Jazmine Sullivan on the Power of Heaux Tales and Singing at the Super Bowl

We hadn’t heard from Jazmine Sullivan in almost six years. The singer-songwriter had spent over a decade gathering commercial and critical success, ever since her 2008 debut with Fearless, only to take a hiatus from her art after the well-received Reality Show in 2015. So when she released a new single, “Lost One,” at the end of last year, it was time.

And yet, I don’t think any of us were prepared. In just 32 minutes, Sullivan's conceptual EP Heaux Tales epically chronicles the experiences of millennial Black women in life and love. Her pen and voice take us on a journey, from “Bodies” opening line, “Bitch. Get it together, bitch” to “I ain't wanna be, but you gon' make a ho outta me” in “A Girl Like Me.” Sullivan's artistry is a North star to a place where Black women’s sexual liberation is the standard, our experiences revered and our stories told.

In short, Heaux Tales did what very few projects can: present Black women as confident, vulnerable, erotic, flawed—whole.

After listening to the project for hours on release day, January 8, I asked if any Black women wanted to discuss it in a community setting. Over 500 women joined me, entertainment journalist Gia Peppers, sex educator and influencer Ashley Cobb, and theologian and life coach Rozella Haydée White on Clubhouse the following day to examine the album’s impact. What happened was nothing short of magical. We shared stories of real joy and great sex. We told tales of unimaginable pain and deep heartache. We shared the stories of Black womanhood, all prompted by the offering of the one who seemed to know us best.

Over Zoom, I had the opportunity to talk with Sullivan about her EP (now number one on Billboard's Top R&B Albums chart), growing up in church and into our own womanhood, and what her upcoming performance of the national anthem at the Super Bowl means to her.

Glamour: How do you feel?

Jazmine Sullivan: I actually didn’t know it would get this response. Because it was an EP, I didn’t know how people would respond to the tales. For me, they were the meat of the project and a huge part of why I even wanted to do this. I needed these stories told. They are personal stories. These are my best friends and members of my family. It started off so small—literally just our regular conversations. I knew it was special to me, but I didn’t know how deep it would be to other women.

But I get it. Our stories aren’t told enough—or at all. We don’t have a lot to be able to say, “Oh that’s me right there.” Or, “That’s my story, and I relate to that.” Or even, “That’s not my story, and I want to know more.” We don’t have enough stories as Black women. I’m happy people are feeling it on a different level outside of the music.

I’ve always considered you a Black girl’s psalmist. You've been able to write our experiences in a way very few can. I think it’s because you don’t shy away from all the parts we try to hide.

JS: I just feel like there are things that need to be said. There’s so much truth to be revealed in the dark places. In order to grow and change, you have to go there. You’ve got to tell the story, and I’m okay with telling it.

In our Clubhouse conversation, so many Black women spoke about their experiences with sexual violence. Then, Antoinette Henry came into the room and shared the context behind "Antoinette's Tale." So many sisters have said Heaux Tales made them believe they can reclaim their power in sexual agency. How much of that figured into your insistence to have those tales be on the EP?

AdvertisementJS: With Antoinette in particular, I’ve always admired her strength. She has a voice that should always be heard. She needed to tell that particular story to bring a different depth to the project. Each woman had something different to offer. I feel like that’s what Black women are. We are not monolithic. We have so many stories. They can be so vast from each other. They may even clash sometimes. That’s what it is being a Black woman.

My favorite part of this project is the Hammond organ playing in the background of “Donna’s Tale.” It’s there because she’s preaching! I’m curious how you’ve worked to reconcile your upbringing in the church and your commitment to tell the stories of Black women, regardless of how church may shape us.

JS: Growing up in church, you know what to say, what not to say, how to act, and what not to do. You base your personality off those things. I was a product of that thinking and would turn my nose up to certain things I hadn’t experienced yet and certain people who were living a life I hadn't lived yet. As I got older and started going through my own shit, I found myself in positions I never thought I’d be in. My eyes were opened.

I had to go through a situation where I felt shame attached to something I did and mistakes I’d made. And I had to come out of that in order to be free and give myself permission to love myself regardless of whatever I’d experienced. I wanted to do that for everybody else. I wanted to tell every young woman, “Yo…you’re okay. You’re figuring it out.” That’s all any of us are doing at any part of our life. It’s about grace.

I do have to tell you this, though. There have been a number of church girls bemoaning the fact they don’t have their own Heaux Tale.

JS: That’s another thing. Growing up in church, we’re told we have to present ourselves damn near perfect. Only then are you considered a good woman and worthy. A lot of us felt like we couldn’t act up if we wanted to. We missed out on a lot of experiences. I think I missed some too.

I did too.

JS: This is definitely a project that gives you permission to do what you want and figure out life the way you want, just like how men are afforded to do all their lives. Men are afforded the chance to walk this life exactly how they see fit, and they’re not judged by it. Women haven’t been given that same room.

AdvertisementI make the argument Heaux Tales needs to be in conversation with Beyoncé's Lemonade as a cultural moment. What’s been exciting for me is that you get to be attached to that moment, because you’ve deserved this a thousand times over. Everybody’s talking about Jazmine, when they should’ve always been talking about Jazmine. Does this feel like a long time coming?

JS: I don’t know if I look at it that way. I feel like whatever I got, as far as notoriety and what people would consider fame, is what I was able to handle at the time. When I started, whatever I experienced is what I needed to experience. What I’m experiencing now is what I can handle.

You’re performing the national anthem at the Super Bowl at a time when the Vice President of the United States is a Black woman. We're at a genuine watershed moment in this country. How do you feel about it?

JS: Honestly, I’ll be the first to say I’ve played myself small all my life. So I never even dreamt of performing at the Super Bowl. I always looked at that as a moment for someone who had a career that was bigger than mine. So I’m just super grateful, in shock, and excited to share this moment with my loved ones who have seen me go through all the things I have in my life. I just feel like it’s all God’s timing because they picked the Blackest, most soulful artist they could find to do this with Eric Church. He’s a country singer, and we are the total opposites of each other. But I’m representing for my people, our lives, our struggles, and everything we’ve been through. I can’t even explain it. I’m completely honored. I’m just gon’ go and sang.

Candice Marie Benbow is a journalist and theologian who writes about Black women’s faith and culture. Follow her @CandiceBenbow.

This story originally appeared on: Glamour - Author:Candice Benbow