Thanks to a global pandemic, the greatest gymnast in history was forced to spend part of the last year finding some equilibrium in a life that had previously been all about the work.

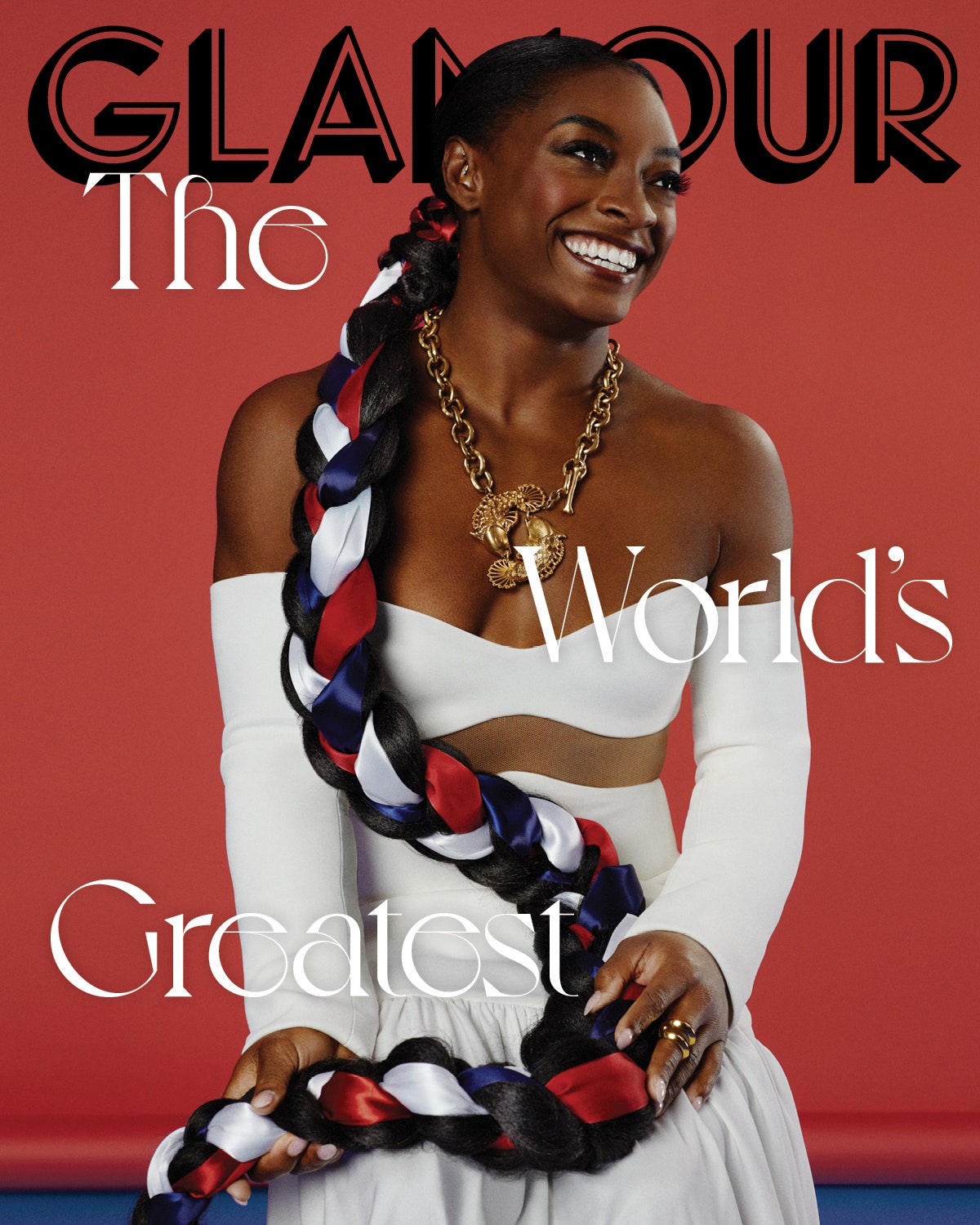

Simone Biles Finds Her Balance

Simone Biles is the greatest gymnast in history. No caveats, no gender qualifiers, no getting around the fact that at 24, she’s broken just about every record there is to break. Twenty-five World Championship medals, four never-before-been-done moves named after her, and a performance level so fearless, it raised the bar for the entire sport. And she’s still at the top of her game, making her one of the best all-around athletes of our time, a competitor whose name will forever belong in the same breath as Serena Williams and Michael Jordan and Michael Phelps.

But for all the gold and GOAT talk, it’s easy to forget that this is a woman who redefined the limits of what the human body is capable of while carrying the mental burden of competing for an organization that failed to protect its athletes—including her—from a documented culture of abuse. And that was before the stress of 2020 hit and the fate of the Tokyo Olympics—which were meant to be Biles’s last—became uncertain.

But more on all that later. Right now Simone Biles is just like the rest of us—signing onto Zoom from home, waiting to get back out there.

During the last year, Biles used her unexpected downtime to buy her own house in Texas, a space she designed for her and her two Frenchies, Lilo and Rambo. This is where she’s sitting when we virtually meet, settled comfortably in a sun-filled room, a loose gray sweater wrapped around her shoulders, at ease in the way we really only ever are in our own space.

Biles spent most of quarantine here during the early, anxious days of the pandemic, but while we were baking banana bread and tie-dyeing sweatshirts, she was grappling with the fact that her chance to finish the career she’d sacrificed her entire life for might be stolen by the pandemic. Navigating a postponement would mean another year of pushing her body to its limit; and Biles’s job relies on her body—a finely calibrated machine conditioned by thousands of hours of workouts to peak at precisely the right moment every four years.

Then it became official: In late March, Texas went under total lockdown. No more training. For seven weeks Biles sat idle, weighing how to commit herself physically and mentally to the uncertainty. It took a toll. “I got to process all the emotions,” she says. “I got to go through being angry, sad, upset, happy, annoyed. I got to go through all of it by myself, without anybody telling me what to feel.”

She became depressed. She thought of quitting. But that didn’t last long. “I wanted to give up,” Biles says. “But it would have been dumb because I’ve worked way too hard.”

The decision to stay in gold-medal shape, even if the next Olympics weren’t for another year, wasn’t just about keeping her 24-year-old body in peak condition. It would also mean shouldering the mental burden of another year of having to compete as part of USA Gymnastics, the governing body of the sport. “I think that’s been the hardest part,” Biles says.

USAG has come under sharp criticism—with many powerful words from Biles herself—for failing to protect its athletes from a documented culture of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. Biles is the only known survivor of sexual abuse who is still actively competing for the organization, according to Insider, and her presence in the gym is a source of constant pressure on both USAG and the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee (also accused of failing to protect its athletes) to conduct further independent investigation. “I’m still here, so it’s not going to disappear—we have power behind it,” she says.

Biles bears the responsibility gracefully, despite the unfairness of asking survivors to be the spokespeople for their own abuse. I ask her how she deals, especially in a sport where mental focus is so important to winning medals. “Probably by compartmentalizing,” she says. “I try not to think about it because I can’t afford to—if I let them rule me, then they’re winning.”

The gymnast has already achieved an unmatched level of excellence, so choosing to put herself through another year was to prove to no one but herself that she could, that at 24 she was better than ever, and that even after everything she’s been through, she still loves her sport. “I know I’m doing it for me,” she says. “I do it because I still have such a passion for it.”

But, after years of the laser focus it takes to be the greatest in history, Biles has also spent the last year finding some equilibrium in a life that had previously been all about the work.

“Before I would only focus on the gym,” she says. “But me being happy outside the gym is just as important as me being happy and doing well in the gym. Now it’s like everything’s coming together.”

Part of this balance includes self-care (baths with Dr. Teal’s), eating Mexican food (“I’m obsessed with cheese, so I start with queso and beef ”), relaxing with her boyfriend (Houston Texans safety Jonathan Owens—they met on Raya), and trying to find a hobby. “I feel like everybody was painting, or knitting, or doing something cool in quarantine, so I was like, ‘I’m going to learn how to do my makeup, my hair, and my nails.’ I almost ruined my nails, so that is no longer permitted. I’ve definitely gotten better at doing my hair, but clearly I’m not gifted in that department,” she says with a laugh. “I’m just really trying to find who I am.”

I ask her when she feels most like herself. “Drinking a margarita at a Mexican restaurant,” she says without hesitation. “That’s me.” (For the record, her signature is watermelon, with a Tajín rim, on the rocks.)

Allowing herself this balance, this ability to be a young woman who can unwind with a good cocktail and a group of friends just as easily as an athlete who can do a double backflip with three twists, took work—and therapy. “I’ve learned it’s okay to ask for help if you need it,” she says.

Biles was resistant to the idea of therapy at first. “One of the very first sessions, I didn’t talk at all. I just wouldn’t say anything. I was like, ‘I’m not crazy. I don’t need to be here,’” she says. But therapy, her therapist explained, wasn’t for people who are “crazy”; it was just an outlet for her to be able to talk about anything going on in her life—gymnastics or otherwise. “I thought I could figure it out on my own, but that’s sometimes not the case. And that’s not something you should feel guilty or ashamed of,” Biles says. “Once I got over that fact, I actually enjoyed it and looked forward to going to therapy. It’s a safe space.”

After the 2016 Olympics, Biles took time off for the first time in her life. “I lived, I traveled, I did things I couldn’t do because of gymnastics,” she says. “I just had fun.”

When she came back to the gym to start training for the Tokyo Olympics—pre-pandemic—she did it on her own terms. “The Simone that I knew and dealt with in 2016 to get her prepared for the Olympics...this is definitely a different Simone now,” says her mom, Nellie Biles.

Now Biles has the benefit of competing as a woman in a sport that prizes youth. “I’m not a little girl anymore. It’s definitely up to me. Nobody’s forcing me,” she says. “Whenever you’re younger, you feel like it’s a job, and you have to be pushed. But now it’s like, This is what I want to do, so that’s why I’m here.” It shows—Biles is one of those rare athletes who looks like she’s having fun at work, making it look less about dominating her competition and more about just doing what she loves.

“Before Simone, nobody had proven that you could be great while being joyful,” says Valorie Kondos Field, the legendary former coach of the UCLA women’s gymnastics team (whom Biles was planning to compete for before she decided to go pro). “If you were going to reach for that level of excellence, you had to be razor-sharp focused 100% of the time. That meant no diversions, no talking to your teammates in training, no cheering on your teammates, because you wanted to beat them.”

Kondos Field remembers a story Biles’s then coach once told her about training at The Ranch (the now shuttered USAG training facility run by former Olympic coaches Bela and Martha Karolyi, where some of the sexual abuse took place), where clapping for other gymnasts was discouraged in order to foster a competitive atmosphere. “It wasn’t like the intention was to make everybody miserable, it simply hadn't been proven yet that you can achieve excellence without having to sacrifice joy in the process,” Kondos Field says. “But Simone did it her way.”

There is an extremely long list of things that makes Biles a sports icon—her strength and speed, her air awareness, her ambition. But it’s her joy, often a radical act for a woman, that makes her such a mesmerizing athlete to watch. At the 2019 World Championships (the one where the death-defying triple double was officially named after her), it would be difficult to watch her routines and not walk away with the impression that Simone Biles is a woman who has found a way to own the thing she loves—to be the unchallenged best and to be happy. “At the end of the day, we train for so long to compete for two, three minutes total. It's like, Where's the fun in that?” she says. “If you're not having fun, it’s not worth it.”

Besides all the medals and the world records, that will be Biles’s legacy—making a space in the world where women and girls can shape their identity with joy and confidence.

That starts at the Bileses’ home gym, which her parents opened in 2015, a sprawling 52,000-square-foot facility designed around facilitating athletes’ health and safety (it includes a training floor enclosed by glass so parents can always watch practices, and an accredited school for elite athletes). “It makes me so proud that we have girls, and boys, that feel good about themselves,” Nellie Biles says. “It’s a culture we’re trying to build; we’re trying to give these [kids] confidence and to maximize their potential.”

After the Tokyo Games—officially taking place in July 2021—Biles is taking over the post-Olympics gymnastics tour, an event that had historically been produced by USAG. The Gold Over America Tour (GOAT for short—see what she did there?) will have lots of dancing, music, and a cast that prioritizes fun over technical superiority (expect another viral Katelyn Ohashi moment). “With what’s happened with USAG, I just wanted it to be completely different, on my own terms. And I think that’s very powerful,” she says.

Biles’s spectacle will feature only women, a choice she feels strongly about. “It’s an all-girl tour for women’s empowerment. It was a great year for women to speak out, and I think it’s nice to keep the ball rolling on that and to have women feel happy, and find their love and passion for gymnastics again,” Biles says. “I know the men were really upset, but it’s my tour.”

But first she has another Olympics ahead of her. “I’ve already done quite a lot, but I’m still trying to reach new heights and see what I’m capable of,” she says. If her recent performances are any indication, Biles really is better than ever. In May, at her first competition since the pandemic began, she landed one of the hardest vaults in history—the Yurchenko double pike, a straight-legged double backflip that requires an insane amount of air—becoming the first woman to ever do it in competition, as the whole world watched slack-jawed from our phone screens. Biles can confidently say she’s done it all, but more than her gravity-defying legacy, she hopes people look back on her career and say, “Wow, she was actually really happy doing this, and she was good,” Biles says. “I think that speaks volumes.”

After two Olympics, the plan was to hang up her grips. “I’m just really excited to see what’s out there in the world and to see what else I’m good at,” she says. But retirement may not be forever. The Paris 2024 Olympics are already tugging at the edges of her brain. “My coaches Cecile and Laurent are from Paris, so I think that would be a good run to end with them there,” she says. “I’ll see where we go.”

Macaela MacKenzie is a senior editor at Glamour.

Photographer: Kennedi Carter; Stylist: Chasidy Chevonne; Hair: Jadis Jolie; Makeup: Ambreen Khwaja; On set production: Bird House Productions; Location: Le Méridien Houston Downtown

This story originally appeared on: Glamour - Author:Macaela MacKenzie