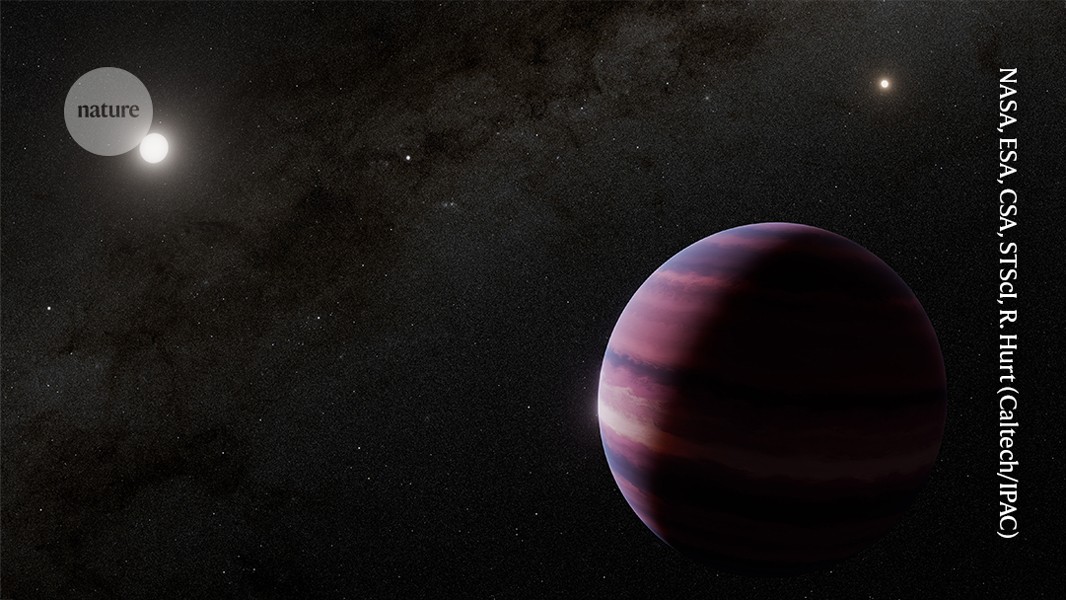

Alien planet glimpsed in star's 'habitable zone'

A smudge of light spotted by the James Webb telescope near Alpha Centauri A could be the planet with the tightest orbit ever to be imaged directly

A glimpse of a planet in its star’s habitable zone — the ‘just right’ region where life could flourish — has astronomers reeling. The smudgy-looking gas planet is circling Alpha Centauri A, the brightest member of a triplet of stars strewn just 4 light years, or 1.4 parsecs, from Earth. And it could be orbiting at a record-breaking proximity to its host star, at least for a planet captured through direct imaging.

Researchers report their findings in two papers due to appear in The Astrophysical Journal Letters1,2.

Most exoplanets are discovered from indirect clues rather than direct imaging. For instance, astronomers uncovered three other planets in the Alpha Centauri system by studying how one of the stars wobbles as it is pulled around by the gravity of the planet orbiting it.

Researchers had the first visual hint of a planet orbiting the star in 2021, using a ground-based observatory3. Now, Aniket Sanghi, an astronomer at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, and his colleagues have used the James Webb Space Telescope’s (JWST) Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) to zero in on Alpha Centauri A.

When a planet orbits close to its host star, astronomers struggle to see it against the star’s glare. That makes it especially difficult to spot a planet that is in the habitable zone, which astronomers define as the range of distances from a star in which water can exist in liquid form on a planet’s surface.

But because the Alpha Centauri system is so close to Earth, JWST managed to get a high enough resolution glimpse of it to pick out the planet — although the team still had to use MIRI’s ‘coronograph’ mode to filter out some of the glare.

The JWST used a 'coronagraphic mask' to block Alpha Centauri A's glare — revealing a possible planet in its orbit.Credit: Science: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, DSS, A. Sanghi (Caltech), C. Beichman (JPL), D. Mawet (Caltech); Image Processing: J. DePasquale (STScI)

Once the planet had been uncloaked, “I was in complete awe”, says Sanghi. “I had to take a moment of silence to appreciate what I was seeing.” To make sure the faint planet wasn’t just distorted starlight, the team spent about a year reanalysing the data. Again and again, the blotch of light remained. “We couldn’t kill it,” Sanghi adds.

Enjoying our latest content?

Login or create an account to continue

- Access the most recent journalism from Nature's award-winning team

- Explore the latest features & opinion covering groundbreaking research

or

Sign in or create an accountdoi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-02549-z

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Jenna Ahart