US and China sign new science pact — but with severe restrictions

Amid tensions, the two nations agree on a path forward for research collaboration

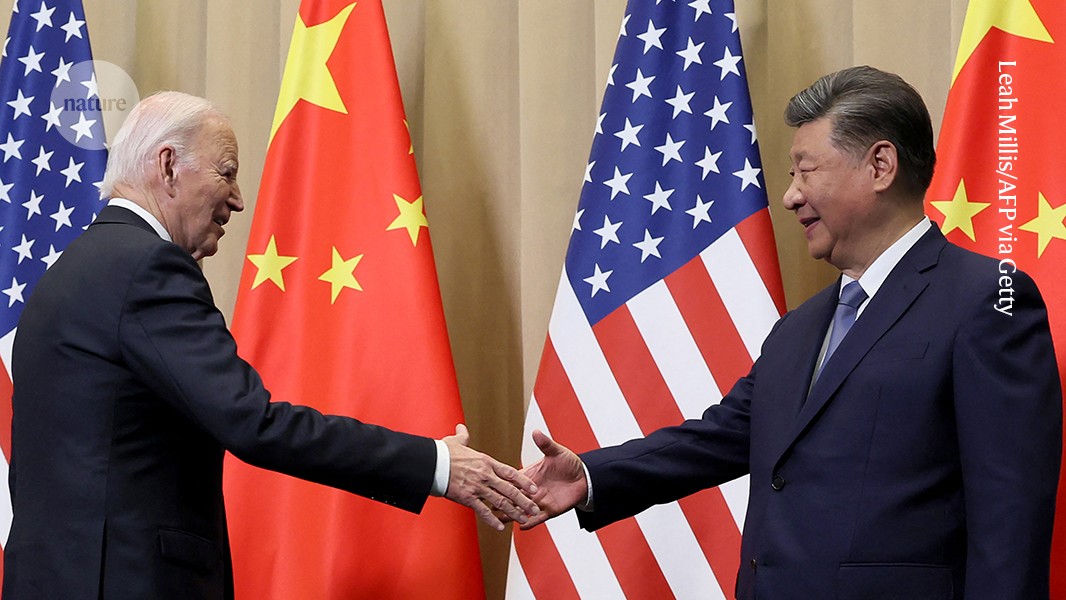

US President Joe Biden (left) shakes hands with China’s President Xi Jinping (right) at an economic summit in November.Credit: Leah Millis/AFP via Getty

The United States and China have signed a brand-new, five-year agreement that dictates how the nations will cooperate on science and technology research. The pact is narrower in scope than its predecessor, covering only collaboration on basic science projects between departments and agencies of the two governments and excluding work on ‘critical and emerging technologies’ potentially important to national security, such as artificial intelligence and semiconductors. Unlike its predecessor, the pact does not include any information about collaboration among Chinese and US universities and private companies.

Experts in US–China relations welcome the agreement, saying that it will enable scientists to pursue projects with confidence.

“I am relieved to see this pact renewal,” says Duan Yibing, a science-policy researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, who hopes the pact will do what it’s designed to: promote collaboration in basic research between the two countries.

“It appears they scrubbed everything and started from scratch,” says Caroline Wagner, a specialist in science, technology and international affairs at The Ohio State University in Columbus. The narrow focus “seems appropriate” given China’s new status as a scientific and economic power. “The United States has recognized its relationship with China is now more symmetrical” than when the original agreement was signed 45 years ago, she says.

The agreement, “demonstrates a pragmatic, if constrained, approach to maintaining scientific collaboration amid geopolitical rivalry”, says Marina Zhang, an innovation researcher who focuses on China at the University of Technology Sydney in Australia.

A modernized agreement

The original pact was forged in 1979 to thaw diplomatic relations between China and the United States. It is normally renewed every five years, but it expired on 27 August last year amid rising tensions. Although the two nations recognized that new terms were needed in the agreement, they were unable to finalize the details before the deadline. Instead, they extended the old pact and kept negotiating.

Researchers and other specialists warned that without the agreement, which is symbolic and doesn’t provide any funding, research cooperation and programmes between the two governments could flounder.

A US Department of State official said at a briefing on 12 December that the government recognized that failure to have an agreement would have a chilling effect on areas of science and technology that are important to the United States. The new agreement is “modernized, with built-in protections”, the official said.

The state department will now vet all research projects to ensure that they don’t pose national security concerns before they are approved. Proposals will also be reviewed by other US agencies led by the White House.

Aside from specifying that critical and emerging technologies are off the table for collaboration, the pact does not further limit which scientific areas are fair game. But a US state department official suggested permissible projects might include research on the weather, oceanography and geology, as well as collecting influenza and air-quality data.

The revamped pact addresses concerns from the United States that China did not always meet its obligation to share data under the previous agreement. The United States has been frustrated, for instance, that China has not been more transparent about data collected by a virology laboratory in Wuhan, where the first COVID-19 cases were detected. Some think that a virus could have leaked from that lab to trigger the pandemic.

The agreement now includes wording that commits both the United States and China to sharing data, and being open and transparent. It also lays out a dispute-resolution mechanism by which both nations can iron out difficulties encountered in projects. If either side does not uphold its commitments, a termination clause allows the nations to end the agreement.

Many of the concerns about the old pact came from the United States, given China’s rise in power. So in these negotiations, China has been “the passive side”, Duan says.

An uncertain future

Because of the timing of the new pact’s signing, one uncertainty hanging over it is whether the incoming administration of president-elect Donald Trump, who will take office in about a month, will uphold it. Researchers who spoke to Nature say they don’t expect the Trump administration to declare the agreement weak and reverse it, given that it already represents a compromise. Also, the agreement was last renewed in 2018 during Trump’s first presidency, Duan points out. Still, he adds, “we have to see what he will do”.

Denis Simon, a non-resident fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, a foreign-policy think tank in Washington DC, says that the new agreement provides “clear guardrails and a path to negotiate disputes”.

Wagner adds that, because they have been excluded from the agreement, universities and private companies will need additional guidance from the two governments on the kinds of cooperation permitted.

Overall, “it’s good news we still have an agreement”, Simon says. “It has been modified to reflect US concerns, but it’s better than no agreement.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-04175-7

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Natasha Gilbert