Powerful satellite will chart changes on Earth’s surface in exquisite detail — down to a centimetre

But will the US–India mission be the last for NASA for a long time to come?

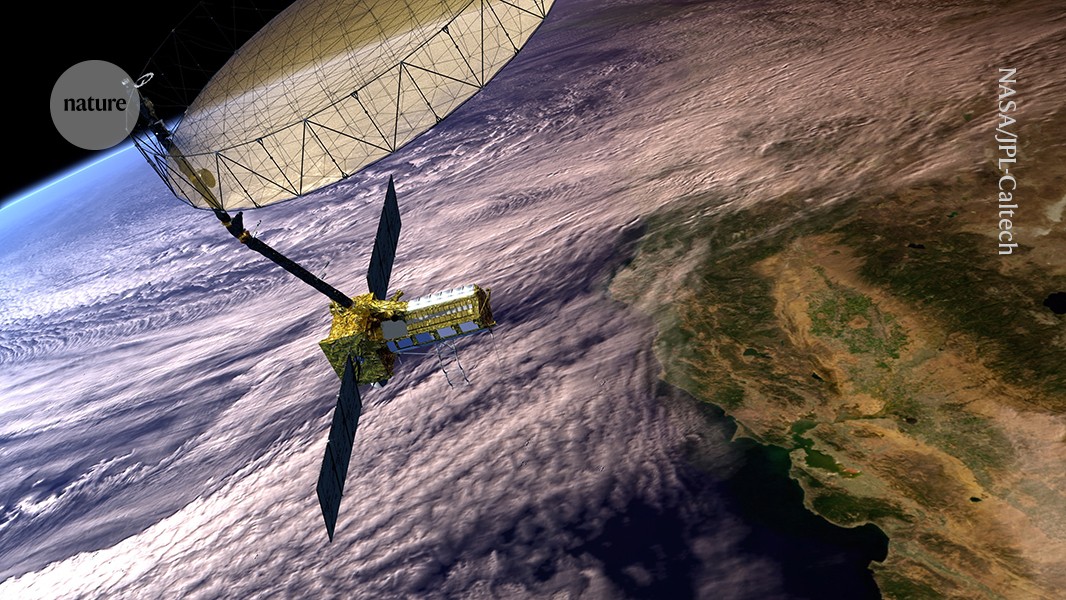

The NISAR satellite (artist’s rendering) will measure physical shifts on Earth’s surface that are as small as one centimetre.Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

An astonishingly high-resolution satellite that launched today will soon map changes on Earth’s surface in unprecedented detail — tracking everything from sinking croplands to crumbling ice sheets and flood-ravaged terrain. It is the biggest-ever collaboration between NASA and the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), carrying with it scientists’ dreams of studying our dynamic planet.

In the coming days, the US$1.2-billion satellite, called NISAR, will unfurl a 12-metre-wide circular antenna and begin bouncing radar signals off Earth. Launched from Sriharikota, India, NISAR will scan nearly all of the planet twice every 12 days, and measure vertical physical shifts on the ground that are as small as one centimetre, even through clouds and at night.

Watching NISAR launch is like being “a parent attending the graduation ceremony of his son!” says Deepak Putrevu, who co-leads the mission’s science team for ISRO. “It’s so exhilarating to witness.”

But for NASA, that excitement is tinged with a dollop of worry as US President Donald Trump pushes to slash the agency’s budget for Earth-science missions by over 50% in the fiscal year 2026. NISAR itself is slated to receive monies to operate as expected, but it might be one of the last of its kind to launch for years: the White House wants to cancel most of NASA’s upcoming flagship Earth-observing missions “to achieve cost savings”. And it wants to shut down several missions that are already operating and gathering key information about changes on Earth.

“This is the size of cut that would fundamentally gut our capacity” to improve understanding of the changing planet, says Dylan Millet, an atmospheric chemist at the University of Minnesota in St Paul who chaired a NASA advisory committee on Earth sciences until March, when NASA disbanded it.

A boost for disaster response

NISAR — which stands for NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar — will use two radar instruments operating at different wavelengths, one built by NASA and one by ISRO, to map Earth’s changing ice and land surfaces. Globally, the satellite will be able to identify changes in soil moisture, forest biomass and glaciers, among other things.

NISAR will be able to measure the movement of ice on Antarctica (shown in this colour map) in detail.Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio

And it will help with response to disasters such as floods, earthquakes and landslides, by providing up-to-date information about how Earth has behaved. “You can begin to build up an ability to see disasters as they unfold at a very rapid pace, and that should help with identifying areas of concern for first responders,” says Paul Rosen, the mission’s project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

NASA and ISRO began collaborating on NISAR in the early 2010s, when it became clear that both US and Indian scientists wanted to fly a major radar mission, Rosen says. If all goes well with the antenna unfurling and other tasks, NISAR should begin providing science data within 90 days. The mission is slated to operate for at least three years.

An uncertain future

What will happen after that is a bigger question, at least for NASA. NISAR was supposed to be the trailblazer in a series of major Earth-observing satellites, aimed at measuring, among other things, the roles of clouds and aerosols in climate change, and biological and geological interactions across the planet.

Enjoying our latest content?

Login or create an account to continue

- Access the most recent journalism from Nature's award-winning team

- Explore the latest features & opinion covering groundbreaking research

or

Sign in or create an accountdoi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-02402-3

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Alexandra Witze