Woman in cancer remission for record 19 years after CAR-T immune treatment

CAR-T-cell therapy treated a girl with a rare childhood cancer, raising hopes for future recipients of the approach

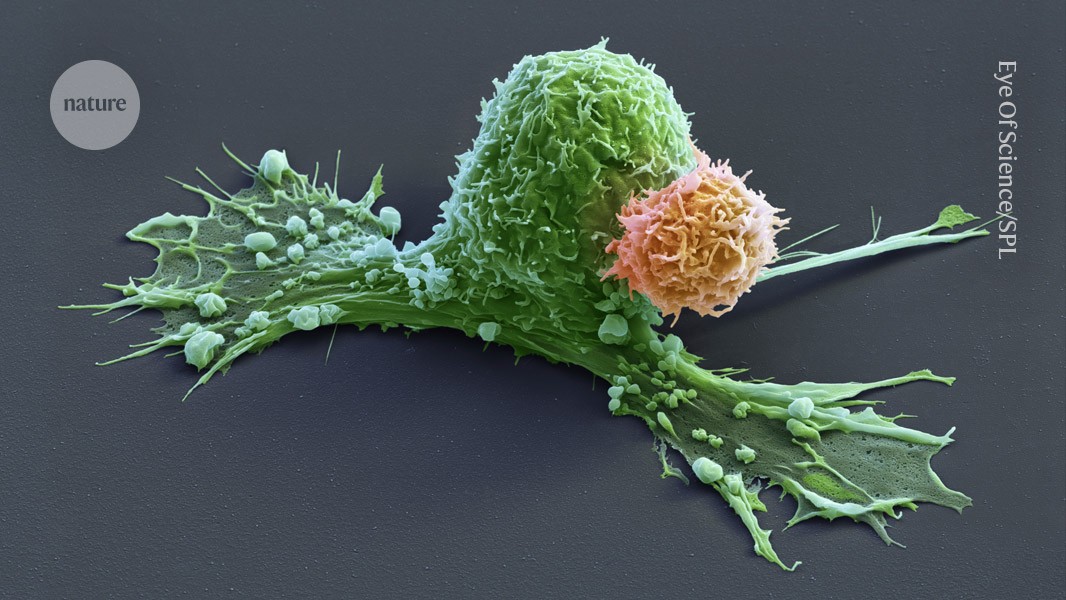

A CAR-T cell (orange) has attacks a cancer cell (green), which is starting to contract.Credit: Eye Of Science/Science Photo Library

The girl was four years old when she arrived at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston to receive a highly experimental therapy for nerve-cell cancer. Standard treatments had been unable to hold the cancer back. It had spread to her bones, and the prognosis was poor.

Nineteen years later, she is cancer-free and the mother of two children. The remarkable success story, published on 17 February in Nature Medicine1, is the longest reported cancer remission following treatment with engineered immune cells called CAR T cells.

In the years since the girl’s treatment in 2006, CAR T cells have produced stunning results in some blood cancers such as leukaemia. Seven CAR-T-cell therapies have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration since 2017, and some early recipients of CAR-T therapy have been cancer-free for more than a decade.

But researchers have struggled to repeat that success against solid tumours such as those caused by neuroblastoma, a nerve-cell cancer that is typically diagnosed in young children. That makes the latest results particularly good news, says Sneha Ramakrishna, a paediatric oncologist and cancer researcher at Stanford University School of Medicine in California, who was not involved in the study.

“This provides me with a lot of hope,” she says. “We’re going to unlock CAR T cells for people with solid tumours.”

Cell target

CAR T cells are immune cells that have been engineered to make a protein called a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR). This protein is designed to latch onto a target found on a cancer cell, triggering the immune cell to attack and destroy it.

When the Texas neuroblastoma study began in 2004, CAR-T-cell therapy was still a bit of a wild idea, says Helen Heslop, an immunotherapy researcher at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, and a member of the team that ran the trial. “This is some kind of weird synthetic biology,” she remembers thinking. “Will it actually work?”

The CAR-T-cell therapies Heslop and her colleagues tested then are now considered first-generation editions of the molecules. Later versions, including those that are now approved medicines, contain extra modifications to bolster their power. Heslop calls her first CAR-T-cell study “a vintage trial”.

Enjoying our latest content?

Login or create an account to continue

- Access the most recent journalism from Nature's award-winning team

- Explore the latest features & opinion covering groundbreaking research

or

Sign in or create an accountdoi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-00507-3

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Heidi Ledford