Here’s how to bag a hefty research prize to turbocharge innovation

‘Challenge’ prizes are growing in popularity, but stimulating creativity takes more than financial incentives

Could you double the lifespan of a mouse, decipher passages in scrolls destroyed nearly 2,000 years ago or, in less than 30 minutes, detect bacteria that cause urinary-tract infections? If so, you would have been eligible to win one of a barrage of ‘challenge prizes’ — the above examples alone provide rewards of more than £12 million (US$15 million). Such prizes have seen a resurgence in the past decade, in the hope that a hefty reward can turbocharge innovation and solve some of society’s stickiest problems.

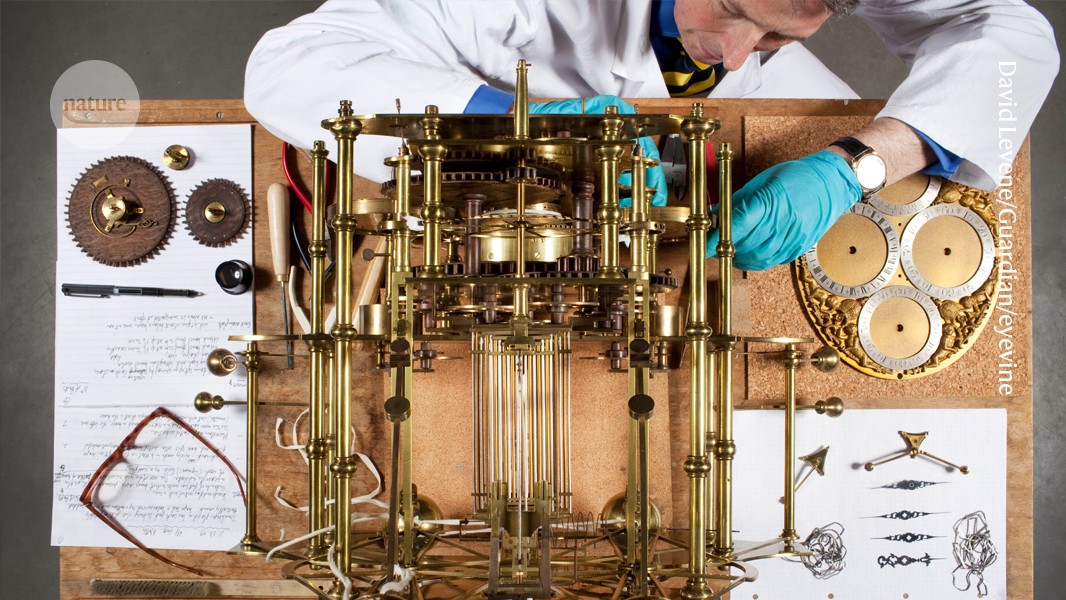

The concept of a challenge prize is not new. One of the most famous examples is the 1714 Longitude prize, offered by the UK Parliament to find a method for determining longitude at sea. More than 50 years later, clockmaker John Harrison won it with a marine chronometer that was able to accurately keep time on a rough sea journey.

The winning solution “changed the world”, says Tris Dyson, managing director of Challenge Works, the London-based non-profit organization that runs challenge prizes across the globe. In 2014, 300 years after the original, Challenge Works launched its own Longitude prize to tackle antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Dyson says that running a successful innovation prize takes a lot more than simply dangling a pot of money, and Challenge Works now provides support ranging from funding grants to community-building events.

The current interest in such prizes came out of concerns that the pace of innovation was slowing, and with public finances becoming more constrained, prizes could offer a cheaper way to stimulate new ideas.

Prizes can de-risk innovation spending, and this is one attraction of the American-Made programme, launched in 2018 by the US Department of Energy to advance technologies to support clean energy. The programme has administered more than 100 prizes, including the annual flagship Solar prize, and has allocated $400 million in prize money. “We reward people for the work that they already do,” says programme manager Debbie Brodt-Giles. “To the government, it’s very low-risk.” The programme also diversifies who is funded by providing a low barrier to entry. “It could be an innovator working out of their garage, or a large-scale company.”

For researchers, it’s a chance to apply their knowledge to real-world challenges and move in a direction that conventional research funding often doesn’t allow. Even for unsuccessful applicants, participation can lead to a start-up venture, an advance in a research goal or a renewed enthusiasm for innovation.

Dyson describes the modern Longitude prize as Challenge Works’ most audacious and high-risk venture. “We didn’t know if we were going to get a winner,” he says.

Encouraging innovators in stages

A partnership with the UK government, the prize featured a public vote on the BBC to select the topic. AMR won, and the £8-million contest was designed around creating an affordable, accurate, rapid and easy-to-use diagnostic test for bacterial urinary-tract infections (UTIs).

Microbiologist Emma Hayhurst took up the challenge. Then at the University of Cardiff, UK, she is now chief executive of Llusern Scientific in Cardiff, a company she co-founded to commercialize the technology she and her collaborators developed. “I can absolutely 100% say that without the Longitude prize, that wouldn’t have got off the ground,” she says. In 2016, she had just returned to science after maternity leave and was looking to kick-start her research by focusing on AMR. She used skills she had already developed in replicating DNA and RNA using loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), a single-test-tube molecular technique that can amplify nucleic acids without having to cycle temperatures. Eventually, she created Lodestar DX, a device that uses LAMP to identify six common UTI-causing pathogens in 35 minutes (J. Diggle et al. JCR-Antimicrob. 6, dlae148; 2024).

The SunFlex team won $650,000 from the American-Made programme for its solar modules.Credit: Sunflex Solar

An important aspect of the competition, Hayhurst says, was the clear requirement that the winning solution should be user-friendly and inexpensive, two of eight mandatory criteria. “It made us focus very early on,” she says, and provided concrete goals.

But having a clear brief and offering a seven-figure reward is often not enough to stimulate innovation, says Anton Howes, head of innovation research at The Entrepreneurs Network, a London-based think tank. People think of the Longitude prize “as a big sum of money that was put up for solving this big problem, and then people came forth with their solutions”, he says. “That’s not really how it works.” The 1714 prize, he points out, awarded small sums along the way to develop promising ideas. Harrison, for example, received £250 in 1737 to improve his sea clock.

The AMR Longitude prize also provided partial funding. “They gave us £16,000, enough to employ a research assistant for 6 months,” says Hayhurst. Unlike a conventional grant, the funding was not dependent on having a proven track record in the field. “Anyone from anywhere can apply, as long as the idea is good,” she says. Her team also sourced small amounts of money from the University of Cardiff and the Welsh government, crucial to help produce a prototype.

The American-Made prizes also provide some funding to help lower the barriers to entry, and the programme employs ‘power connectors’ — people who help with outreach and the recruitment of innovators beyond the organization’s typical networks.

Holly Jamieson, executive director of Challenge Works, says that many of its prizes now include more competition stages: the organization funds an initial cohort that is whittled down, with increased funding at each stage. Challenge Works used this model for its second Longitude prize, launched in 2022, which offered £4.4 million to create technology to help people with dementia live independently. In 2023, 24 semi-finalists each got £80,000 to produce a prototype, with five finalists then getting £300,000 each to develop innovations such as smart glasses to aid memory and a remote safety-monitoring system. The winner, to be announced next year, will get £1 million. Similarly, the American-Made Solar prize awards 20 first-stage competitors $50,000, ”enough to keep them energized and working towards that next goal”, says Brodt-Giles, with $100,000 for ten finalists and then two final $500,000 prizes. The competition also awards vouchers that grant access to US national lab facilities to help accelerate innovations.

The 2022 winner, Origami Solar, based in Bend, Oregon, produces steel frames that house solar panels and that use less materials than existing set-ups, drastically lowering the carbon footprint of installation. The company received $150,000 in vouchers which it used at Sandia National Laboratory in Albuquerque, New Mexico, to investigate whether the frames could be used in any climate. “Solar can provide energy in even extreme climates, but you have to have panels able to handle snow loads,” says founder Eric Hafter. “With Sandia, we’ve been doing extensive snow-load testing.”

Hafter says the competition has been central to their success. “That level of validation was like going from a stationary concrete diving board to a springboard, something that really gave us so much more momentum.”

Runner-up rewards

Environmental systems modeller John Gallagher, at Trinity College Dublin, vied for one of the first European Commission Horizon prizes. The 2018 award was €3 million (US$3.1 million) for ways to reduce the concentration of particulates in urban areas. He had been working for several years with a colleague to provide a pre-filtration process for mechanical ventilation systems in urban buildings, to remove particulates from the air.

Gallagher received funding to move his ideas forwards, and says that compared with other European funding, the prize “didn’t have the same level of reporting required around it, which was fantastic”. His team’s prototype reduced the energy consumption of ventilation systems by one-third and was one of only two to progress to the final stage, but the prize ultimately went to a large multinational company. “We went to the ceremony and sat beside the winner and clapped for the winner, and they received €3 million as a company, and we received zero,” he remembers. “I think that was the hardest part”, because both teams’ work contained innovations. Hayhurst also missed out on the Longitude prize but feels her team came close. “I’d love it if there were second and third prizes, not just all to one winner, because I feel that we could have done an awful lot with even some of that money.”

Innovator and entrepreneur Emma Hayhurst.Credit: Llusern Scientific

Unlike Hayhurst’s, Gallagher’s innovation ultimately stalled for lack of more-substantial funding. Undeterred, he is now competing in Science Foundation Ireland’s Sustainable Communities Challenge. His team’s entry is a phone app that helps rural communities to manage water scarcity, contamination and infrastructure issues, using real-time monitoring and artificial intelligence for better decision-making. It is one of 12 projects to make the penultimate round, each of which was awarded €250,000.

Even if he doesn’t win this time, Gallagher says that taking part in these competitions has made him keener to explore the commercial opportunities that arise from his research. “It can accelerate real-world impact” more so than continuing at the pace of basic research, he adds.

In the end, the 2024 AMR Longitude prize was awarded to diagnostic company Sysmex Astrego, based in Uppsala, Sweden. Its PA-100 AST point-of-care test captures bacterial cells directly from urine samples using a microfluidic chip, and monitors their growth rates when exposed to nine antibiotics (Ö. Baltekin et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 9170–9175; 2017), to indicate which drug should work best against a UTI.

Originally called Astrego, the firm was acquired by a Japanese company called Sysmex in 2022, which helped it to grow. But being part of the competition provided the company with both external validation and inspiration for its technology. “It gives some legitimacy to what we’re doing, that this is something that is needed,” says chief executive Mikael Olsson. “It has motivated a lot of people within the team.”

Contests that spur collaboration

Do challenge prizes elevate competition above cooperation? They are competitive, especially in the later stages, agrees Dyson, but earlier on, “can actually be quite collaborative”. Jamieson adds that there are cases of teams combining during Challenge Works competitions.

The Vesuvius Challenge successfully blended competition and cooperation in its contest to use machine learning and computer vision to read the Herculaneum scrolls that were buried and carbonized by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in ad 79. “For me, this is the gold standard” of how a challenge prize should be run, says Howes.

Enjoying our latest content?

Login or create an account to continue

- Access the most recent journalism from Nature's award-winning team

- Explore the latest features & opinion covering groundbreaking research

or

Sign in or create an accountNature 638, 845-847 (2025)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-00461-0

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Rachel Brazil