Why are proponents of ‘smart cities’ neglecting research?

Despite the buzz surrounding smart cities in urban-policy circles, studies are lacking on the evidence for what works, what doesn’t — and who benefits

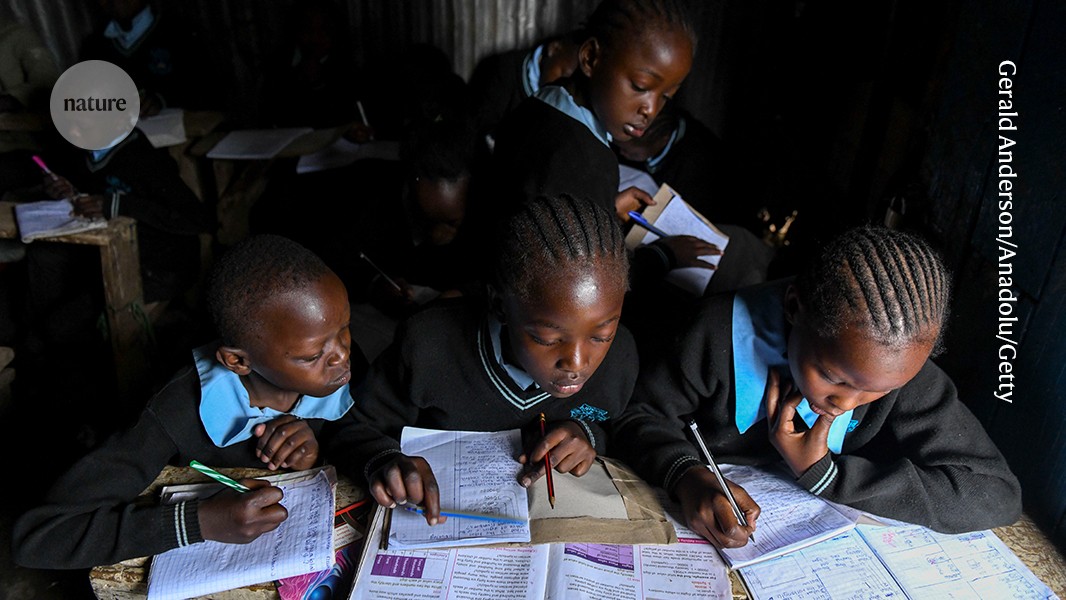

Residents of Kibera in Nairobi are using digital technologies to advocate for better public services, including schools.Credit: Gerald Anderson/Anadolu/Getty

It has been at least 50 years since examples of what we now call ‘smart cities’ began to appear. In 1974, officials in Los Angeles, California, used IBM mainframe computers to study poverty in the city. They analysed demographic data on factors such as infant mortality, household incomes and the standard of housing to identify areas in need of assistance. At the time, computers were expensive and more likely to be found in large corporations and fields such as finance and defence. Using them to tackle poverty was an innovative and ‘smart’ thing to do.

Today, officials around the world have plans to transform many city regions using technology — which is one definition of a smart city. A few years ago, engineer Jose Montes at the University of Quebec Trois-Rivières in Canada counted 28 definitions (J. Montes Preprint at SSRN https://doi.org/n9xt; 2020).

Among the locations are futuristic cities such as The Line, which is being developed in Saudi Arabia, near the Red Sea, by the state-owned company Neom. It will comprise a car-free urban space, standing 500 metres tall and stretching for 170 kilometres, powered wholly by renewable energy. The intention is to create urban living while preserving nature, Neom executive Denis Hickey told the World Economic Forum in January.

The long-running Map Kibera project in Kenya offers a completely different example. In this scheme, residents of Nairobi’s slums are collecting data on topics such as the quality of local schools and the availability of water, and submitting these to policymakers to push them to improve public services. A mobile app called Kyiv Digital is yet another example. It provides air-raid alerts and the locations of bomb shelters, as well as the whereabouts of food and medical supplies, for the Ukrainian city’s population of some 3 million people.

Many governments see both technology and cities as drivers of growth, and have been working to emulate US cities such as San Francisco in California and Cambridge, Massachusetts, which are famous for the confluence of universities, entrepreneurs and capital that has spawned the creation of technology corporations. The BRICS group of countries — named for its early members Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa — have gone as far as creating a BRICS Smart City Ranking to benchmark their progress against each other.

Despite all this interest, however, large parts of the world are underserved when it comes to published research on smart cities and related fields. The scarcity of research was highlighted earlier this month by a systematic review of the literature on 16 southern African countries, published as part of a Focus on smart cities in the journal Nature Cities (see go.nature.com/4hqion4). Federica Duca at the University of Johannesburg in South Africa and her colleagues assessed more than 100 studies, including policy reports and journal papers, from between 2010 and 2023. The majority of the studies were on, or from, South Africa. Most other southern African countries either did not feature at all among the journal articles, or were the focus of only a handful of studies.

The authors also found that much of the work focused on infrastructure, particularly in the academic literature, with comparatively less on the costs and benefits of smart cities. They did, however, note that studies have “questioned whether the promised benefits of smart cities have been realized”, and they recommend that future studies “take into account the role of conflict and of authoritarian regimes, as well as nation-building intentions” (F. Duca et al. Nature Cities 2, 149–156; 2025). The Line is an example of a project in need of such analyses.

A United Nations initiative should help to raise the profile of relevant research. Later this year, UN-Habitat, the UN agency for sustainable cities, based in Nairobi, will finalize its guidelines for the development of what it is calling “people-centred smart cities”. The guidelines are an attempt to create what UN-Habitat’s Isabel Wetzel calls “a universal language and understanding” of what a people-centred smart city is — one that prioritizes peoples’ needs, human rights and well-being, as well as environmental sustainability, while including people in decisions that affect them.

The guidelines include the need for research — for example, the study of community perspectives in policy development, and assessments of the environmental impact of technologies. UN-Habitat needs to ensure that research is central to its vision. Research is key to knowing what works and what doesn’t, who benefits and who doesn’t, and what the consequences, both intended and unintended, of particular smart-city policies might be.

Nature 639, 276 (2025)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-00727-7

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:furtherReadingSection