A family affair: how scientist parents’ career paths can influence children’s choices

Early exposure to science inspired four researchers to pursue research careers

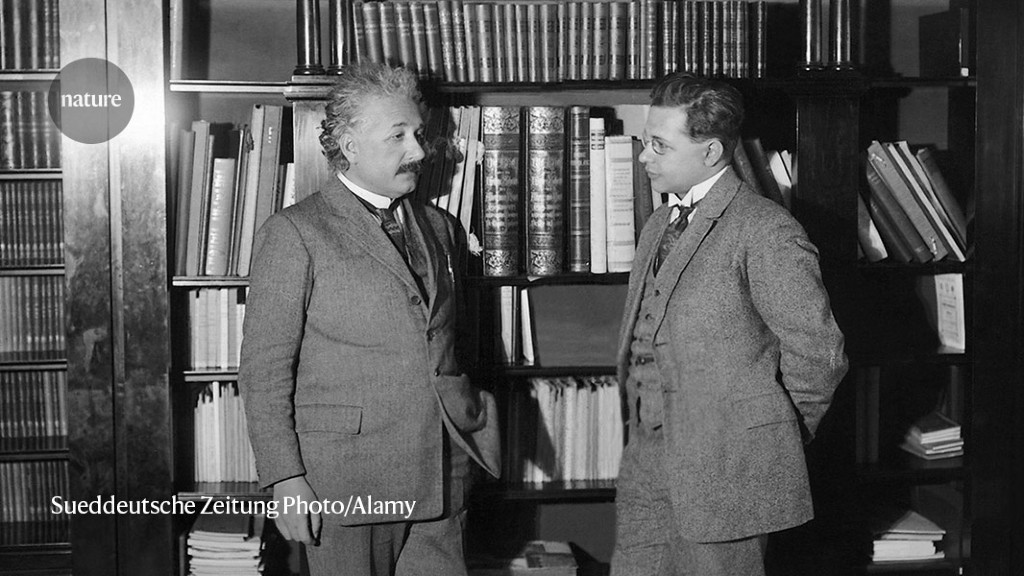

Albert Einstein and his son Hans-Albert both pursued distinguished careers in science.Credit: Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo/Alamy

Children whose parents have science degrees are twice as likely to pursue science degrees themselves than are those whose parents have degrees in other fields (N. Tilbrook and D. Shifrer Soc. Sci. Res. 103, 102654; 2022). Scientist parents can be role models for their children and often provide early exposure through science-focused extracurricular activities. Their children can see at first-hand the highs and lows of a career in academic and industry research — the discoveries, collaborations and opportunities to live and work abroad. But that can be tempered by intense workloads, temporary contracts, pressures to publish and time away from families.

Four researchers share how their parents influenced their choice of a research career and how their own parenthoods have influenced their science.

FRED CHANG: Respect personal choices and decisions

Professor of cell and tissue biology at the University of California, San Francisco.

My parents immigrated from Taiwan to the United States in the 1950s to pursue graduate studies in engineering. My father, David Chang was a mechanical engineer who started a company in our garage, so my childhood was surrounded by electrical machinery and tools. My mother, Helen Chang, worked as a staff scientist at a diabetes lab at Stanford University in California. She introduced me to the environment of a biomedical lab and trained me to work in one. My parents placed a high priority on getting me the best education possible and gave me opportunities to broaden my education in maths and science.

In my early 30s, I married and had two children. I am a cell biologist and my ex-wife is a professional musician, so my daughter and son grew up with both music and science at home. They spent many formative summers with me at Woods Hole in Cape Cod, where I work as a summer investigator at the Marine Biological Laboratory. Woods Hole is like a summer camp for scientists, and my children got to see how much fun I had making discoveries while collaborating with friends and colleagues.

Woods Hole also operates a science school at which my children learnt how to observe and explore the rich natural environments at the seashore. They’re now in their late twenties. My daughter has always been fascinated by the history of Earth, and she’s now a geologist. My son is a mechanical engineer who enjoys the practicality of building structures.

In my 40s, I came out as a gay man. It was an extraordinarily difficult process that took many years; I regard my coming out as my most courageous act. Although this was a challenging time for everyone in the family, we gradually adapted to the changes. My children have been an important source of support, and they fully support me and my partner. I would like to think that seeing me navigate my identity has had a positive influence on my children. Both have grown to be empathic and respectful humans.

Fred Chang (left) with his parents and two children.Credit: Fred Chang

LOTTE DE WINDE: Learn to compartmentalize and prioritize

Research associate at Amsterdam UMC location VU in the Netherlands.

My father is Han de Winde, a biotechnology researcher at Leiden University in the Netherlands. My mum trained as a paediatric nurse and has been working for almost 25 years as a nurse practitioner. Her name is Marga de Winde-van Zijl. When I was born, my dad was pursuing his PhD, but even after he became a professor, he did not miss any important moment of my life. He has shown me that it is possible to balance work and life well and how compartmentalization can help to achieve that. During my school holidays, I used to join my dad at work. I used to refill his pipette-tip boxes, for example, and I enjoyed being in the lab environment. Later, he took me to open days at various Dutch universities, where we participated in medicine and science-related programmes and activities.

I initially wanted to become a physician, but as an undergraduate, I was deeply drawn to the study of our immune system. I wanted to understand why a system that is made to keep us healthy was failing to eradicate cancer. Now, I study lymphoma. My father read my applications to graduate school and gave me advice on how to strengthen my personal statements to show my interest in research. My parents also encouraged me to try my hand at many things. As a parent of a 1.5-year-old daughter, I want to be able to do the same for her.

I will fully support my daughter if she chooses a similar career, because research can have a positive impact on society and it’s great for someone with a curious mind. But most if all, I want her to do something that makes her happy, whether in science or other fields.

Deciding to start a family was not an easy decision. My partner and I have been together since 2009 and moved to the United Kingdom in 2017. We decided to start a family only after returning to the Netherlands in 2020. We felt that we had better job security there, and were closer to our families. There is also a commonly accepted practice for new parents to work four days in the office or the lab in the Netherlands, so that they can spend more time with their children in the early years of their life. These conditions gave us the confidence to start a family.

Becoming a parent has taught me a few valuable lessons that have benefited my work. I have learnt to compartmentalize my roles at work and home. I used to feel guilty when I was at work, because I could not take care of my child, yet I also felt that I was not giving enough time to my research. After I decided to give 100% to my research when in the lab and 100% to my child when at home, it improved my work productivity and the quality of my family time.

MARK PRAUSNITZ: Parenthood has parallels with professorship

Regent’s professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta.

I grew up near the University of California, Berkeley, where my father, John Prausnitz, a chemical engineer, is now an emeritus professor. My late mother, Susan Prausnitz, was a paralegal. Many friends in their social circle are also researchers. Living in that environment gave my elder sister and me an early glimpse of what a career in science would be like. This influence was through soft power that focused on people and the joys of science rather than on hard technical content discussed over dinner or used as a lens for interpreting the world. My sister became a health-care researcher and I decided to follow in my father’s footsteps and become a chemical engineer.

A lesson I learnt from my father is epitomized by his lecture entitled ‘Chemical engineering and the other humanities’, which he gave several times in the 1990s. Although I was already a young professor when he gave this particular lecture, he has been conveying the messages in it to me in direct and indirect ways ever since I was a child. In particular, he explains why scientific research is ultimately a human endeavour that affects society and how society in turn affects science. This perspective has influenced the research I do, which is to adapt engineering technologies to improve drug delivery and other medical interventions through simple, low-cost solutions that improve patient access.

My training as an engineer influences my mentorship style at work as well as my parenting at home. Engineering often emphasizes efficiency and teamwork to complete large projects, and this approach influences how I run my lab. I seek to prioritize activities that require my involvement and delegate others between the 26 members of my research group. This approach has spilled over into my home life with my wife — public-health professional Cindy Weinbaum — and three children. My wife and I needed to identify which activities we would prioritize doing with our kids, and which ones we might delegate, such as shuttling them to and from after-class activities when they were young.

Similarly, being a parent has taught me to be a better researcher. One of the great parallels between parenthood and being a professor is mentorship. I run my lab as a mentor, not a boss. I guide my students and postdocs in their research, offering suggestions (with varying levels of urgency) and helping them to become independent researchers. This mentorship style is also reflected in my parenting, and I see myself guiding my children to independence, too. It’s a great feeling to see my children and my lab members grow and go on to make their own impacts on humanity.

Valerie Yang Shiwen with her partner, Alexander Yap, and son.Credit: Yan Jiejun

VALERIE YANG SHIWEN: Be disciplined and choose what’s right for you

Assistant professor at the National Cancer Centre Singapore.

I remember a story from a colleague who was throwing a retirement party for a prominent professor. When invited to join, his children said that they didn’t want to attend the party because their father had dedicated so much of his time to work that they did not feel that he was actually a father to them. This incident left a deep impression on me, and it reminds me not to further my career at the expense of my family.

Both my father, Joseph Yang, and my mother, Theresa Yap, were general practitioners, so becoming a physician was a natural career decision. However, my dad would often encourage me to go into scientific research, telling me tales of the limitations of medical practice. For instance, he described how he would experiment with a combination of different off-the-shelf creams to achieve the best results for his patients with recalcitrant eczema, yet be unable to decipher why some patients fared better than others. Eventually, I split the difference and started studying for a PhD in oncology at the University of Cambridge, UK, in 2006.

I had my son in 2016, during my clinical specialty training, and received my first independent grant the day before I gave birth, so had to deliver both the baby and the research. After three months of maternity leave, I went back to work, and I saw myself missing some of my son’s important milestones, such as sitting up independently, rolling, babbling and trying different foods for the first time. I was leaving for work before 5 a.m. and not returning until past 11 p.m., and often had to stay in hospital overnight on-call for either ward or intensive care unit coverage. So I decided to take six months of unpaid leave so that I could spend quality time with my son. It certainly felt like I was jeopardizing my career by delaying the exit exam for my clinical specialty, but I now know that I made the right choice. I cannot not turn back the clock to witness my son’s milestones that I would otherwise have missed, but there would always be other grants and opportunities for me to grow my career.

Parenthood has taught me to be more disciplined in my work and to dedicate my time and limited resources to projects that really matter the most to me.

Nature 618, 635-637 (2023)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-01939-5

These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Andy Tay