AI and misinformation are supercharging the risk of nuclear war Scientists must speak truth to power

Emerging dangers are reshaping the landscape of nuclear deterrence and increasing the threat of mutual annihilation

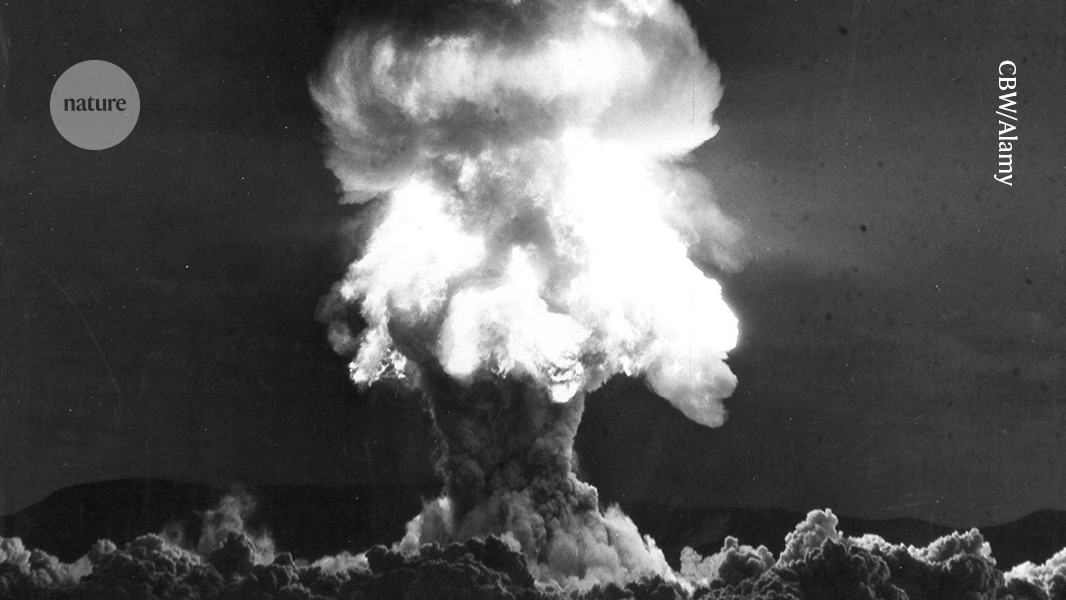

The first-ever nuclear explosion at the Trinity test site in New Mexico, July 1945.Credit: CBW/Alamy

The world entered the nuclear age 80 years ago this week, when the US military tested the first atomic bomb at the Trinity Site in the New Mexico desert. Just three weeks later, US bombers dropped nuclear warheads on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing hundreds of thousands of people.

The threat of mutual nuclear annihilation has been present ever since, most notably at the height of the cold war, as the United States and the Soviet Union built up huge arsenals to deter the other from using them. Today, there are nine nuclear-armed nations — the United States, Russia (inheritor of the Soviet Union’s stockpile), China, France, the United Kingdom, India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea — and the risk of nuclear war is higher than it has been in many decades.

That much was made plain in a gathering of nuclear-security specialists and Nobel laureates this week at the University of Chicago, Illinois. The problem is not only the 12,000-plus nuclear warheads in existence, or the enmities of some governments who command those arsenals. It is also the rise of technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and the rampant spread of misinformation, as Nature reports in a News Feature. These can fuel tensions between nuclear-armed nations, disrupting the delicate balance of nuclear deterrence and increasing the odds of a hair-trigger attack. Scientists must now draw wider attention to these emerging dangers and increase pressure on leaders to respond appropriately. Humanity must avoid the most profound and world-altering possible consequence of inaction: nuclear war.

Ever since scientists developed the first nuclear weapons as part of the Manhattan Project, academics have concerned themselves with nuclear security and non-proliferation. In July 1955, ten years after the Trinity test and during the height of hydrogen-bomb testing, fission pioneer Otto Hahn led a declaration at the annual meeting of Nobel laureates, in Lindau, Germany, that condemned the lethality of nuclear weapons. That same month, physicist Albert Einstein and philosopher Bertrand Russell evocatively warned of nuclear war as “universal death, sudden only for a minority, but for the majority a slow torture of disease and disintegration”.

This Russell–Einstein manifesto led to the first Pugwash conference in 1957, named after the village in Canada where it was held. It remains an ongoing series of gatherings of leading scientists to discuss and warn of nuclear threats.

This week’s Nobel Laureate Assembly for the Prevention of Nuclear War in Chicago follows in this tradition. The participating scientists issued a declaration listing urgent steps for countries to take, including reiterating commitments to ban nuclear testing and condemn proliferation by any state. Other action points include calling on the United States and Russia to immediately enter negotiations for an arms-reduction treaty to succeed the 2010 New START treaty, which expires in February 2026, and for China to engage in transparent discussions about its growing nuclear stockpile (see go.nature.com/3nwqfn6).

Nukes and bots

Researchers told Nature that today’s volatile geopolitical landscape is a major risk for nuclear war. Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, North Korea’s slow but steady escalation of its nuclear arsenal and the Israeli and US attacks on Iran’s nuclear facilities in June have created a tinderbox of uncertainty. AI and misinformation could ignite it.

In May, for instance, during a short-lived but dangerous conflict between India and Pakistan, news and social-media feeds in both countries were flooded with fake photos showing damage from military strikes. A continued deluge of false news, including doctored images in the middle of an active conflict, increased the risk of a nuclear escalation. Nuclear deterrence depends on a clear understanding of an enemy’s capabilities and intentions. The incident highlights the danger of misinformation thickening the fog of war, raising the risk of misunderstandings.

And then there is AI in warfare. Militaries around the world are already using AI in conventional warfare, for example to analyse streams of intelligence data or speed up early-warning systems. Details of how AI is being used in nuclear-weapons operations are shrouded in secrecy, but many, if not most, nuclear-armed nations are almost certainly incorporating it. The concern here is not so much the risk, in the bleak joke of the moment, of giving the launch codes to ChatGPT, but that the speed of AI-assisted decisions coupled with potential errors from AI magnify the risk of mistakes in what are already life-and-death decisions in military operations.

Researchers, policy specialists and government officials must talk regularly and transparently about the use of AI in the military. This can take place through venues such as the ongoing summits on responsible AI in the military, the next of which is slated for September in Spain, or through informal dialogues at disarmament talks.

This week’s Chicago declaration has laudably called attention to a modern nuclear landscape. Now, it’s up to researchers to make good on these actions, says Brian Schmidt, an astrophysicist at Australian National University in Canberra and co-organizer of the meeting. Scientists must take their expertise to their political leaders and ensure that nuclear weapons will never be used again.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-02271-w

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:furtherReadingSection