Should young kids take the new anti-obesity drugs? What the research says

Evidence shows that blockbuster weight-loss medications can reduce obesity even in children aged 6–11, but their long-term effects on growing bodies are unknown

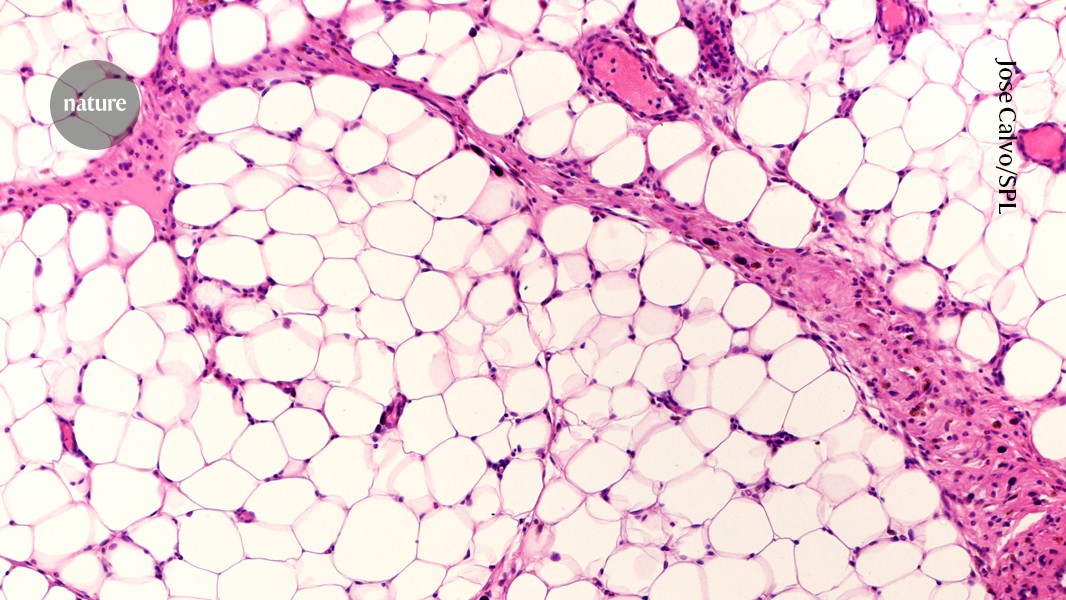

Adipose tissue, or fat, is not always accurately measured by the metric called body mass index.Credit: Jose Calvo/Science Photo Library

Millions of adults around the world take potent drugs such as Wegovy to shed pounds. Should kids do the same?

That question is growing more urgent in the face of mounting evidence that children and adolescents, as well as adults, slim down if they take the latest generation of obesity drugs. Clinical trials1,2 have shown that many adolescents with obesity lose substantial amounts of weight on these drugs, which work by mimicking a natural hormone called glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). The GLP-1 mimics semaglutide, commonly sold as Ozempic and Wegovy, and liraglutide, marketed as Saxenda and Victoza, are approved in the United States and Europe to treat obesity in children as young as 12.

Now a trial has produced some of the first data on anti-obesity drugs in even younger children: those aged 6 to 11. The study3 reports that children who were treated with liraglutide showed a decrease in their body mass index (BMI), a measure of obesity. The results were published on 10 September in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Nature asked specialists in obesity about the costs and benefits of giving the GLP-1 mimics to youngsters who are still growing and developing.

Why test powerful weight-loss drugs on kids?

Most kids with obesity become teens with obesity and then adults with obesity. Many young children with severe obesity have “already developed significant health issues”, says physician Sarah Ro, who directs the University of North Carolina Physicians Network Weight Management Program and has served as a consultant to Novo Nordisk, the manufacturer of semaglutide. Her clinic in Hillsborough treats children with severe obesity who have health issues such as high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes or an advanced form of liver disease linked to excess weight.

There aren’t great options for effectively treating kids with obesity, Ro says. Families are asking for intervention, adds paediatric obesity researcher Geoff Ball at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada, who has also worked as a consultant for Novo Nordisk, but data on how the youngest kids react to obesity drugs are scarce.

“We know that a lot of the decisions doctors make are based on trials in adults,” he says. “We need to have evidence from children to inform clinical decision-making.”

How effective are these drugs in kids and teens?

In last week’s study3 of children aged 6–11, 46% of the participants who received liraglutide saw their BMI fall by 5% or more, compared with 9% of those who received a placebo.

“Our team was delighted to see the results of this clinical trial,” says Ro.

But 72% of the 82 participants in that study were white, and only 6 individuals were Black, so the results might not generalize to children of colour. More diverse studies are needed, Ball says.

Findings in older children have been similar to those from the latest trial. A 2020 study1 investigating liraglutide in 12–17-year-olds found that 43% of those who took the drug showed a reduction of at least 5% in their BMI, compared with 19% of those who were on a placebo. And in a 2022 trial2, 73% of participants aged 12–17 who took semaglutide lost 5% or more of their body weight, compared with 18% of those taking a placebo.

Is BMI the best choice of metric?

The latest trial’s strategy of using BMI to measure progress has disadvantages, scientists point out. “BMI is not perfect. For kids, because they’re growing, it’s not an ideal metric,” says Ball. “We know that BMI is a poor surrogate for fat mass,” wrote the authors of an editorial4 that accompanied the findings.

Sarah Nutter, a weight stigma researcher at the University of Victoria in Canada, says that obesity should be defined by weight-related health problems. The authors of the study should have used a more reliable indicator of health than BMI, she says.

The study’s authors did not respond to a request for comment on the use of BMI.

How much is known about these drugs’ long-term consequences for pre-adolescent children?

Not much. “We do not have long-term data on the effects [of GLP-1 mimics] on growth and puberty on these young children,” says Ro. That’s partly because the drugs are relatively untested in the youngest people. For example, none of the GLP-1 mimics have been approved in the United States for treating obesity in kids younger than 12.

The children who took part in the latest study received liraglutide for just over one year and were followed for another six months. The study’s authors plan to continue to collect data on the drug’s safety until January 2027.

Ro calls for prolonged monitoring of the study participants to look for any signs of eating disorders. The GLP-1 mimics “are powerful drugs, and we need to wade carefully”, she says.

Once kids start these drugs, are they expected to take them for their whole lives?

GLP-1 mimics are currently considered lifelong drugs. “Obesity is a chronic progressive relapsing disease that requires ongoing treatment,” says Ro. But, in practice, some children will need to stop taking the drugs — when their families lose insurance coverage, for example, or if the negative side effects, such as nausea, become intolerable. What the exit strategy would look like for kids is a key question for further research.

“Once patients stop taking the GLP-1 drugs, the hunger and craving return and thus patients start regaining the weight,” says Ro.

Does giving these drugs to minors raise any ethical concerns?

“That’s something that we’re going to have to wrestle with,” says Nutter.

Nutter has reservations about obesity drugs in general, and especially for children and adolescents, whose bodies are still developing. She is also concerned that families might make decisions on the basis of weight stigma, rather than looking at whether a child — at whatever weight — is healthy. Families are steeped in “a culture that glorifies thinness and criticizes and shames people who have higher body weight”, she says.

The children Ro treats, who can experience “incessant bullying by peers”, know all about that. “No one seems to be talking about the risks of doing nothing,” says Ro. Carrying 250 pounds (113 kilograms) on a 10-year-old body can affect growth and puberty, not to mention the heart, lungs and kidneys, as well as mental health and lifespan, she says. “As in all things,” she adds, “we need to weigh the risks and benefits of treatment versus no treatment.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-02983-5

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Julian Nowogrodzki