The surprising link between gut bacteria and devastating eye diseases

Finding raises hopes that antibiotics could treat some genetic diseases that can cause blindness — but also prompts doubts

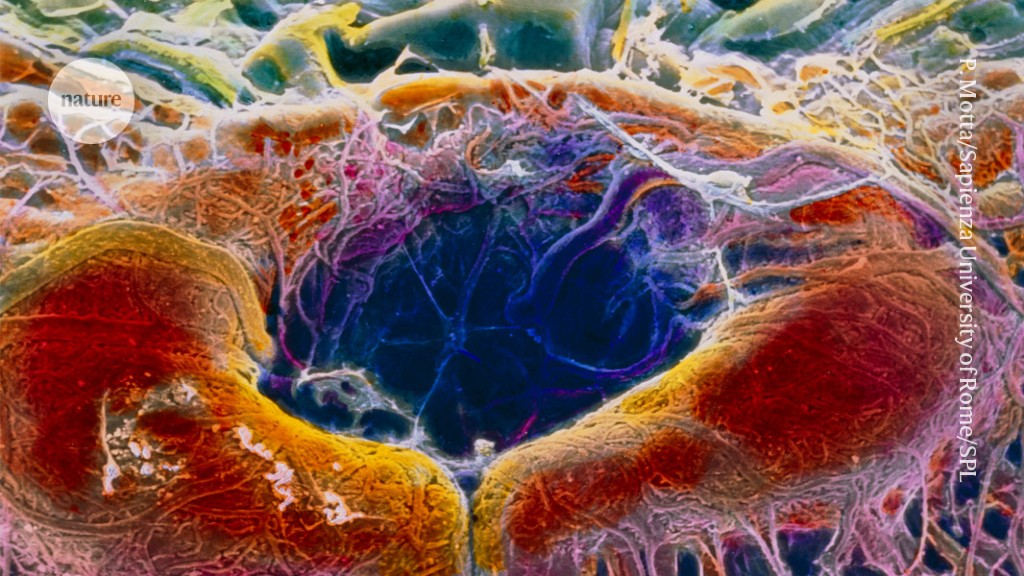

The region of the retina called the central fovea (pictured, artificially coloured).Credit: Prof. P. Motta/Dept. of Anatomy/Sapienza University of Rome/Science Photo Library

Eye diseases long thought to be purely genetic might be caused in part by bacteria that escape the gut and travel to the retina, research suggests1.

Eyes are typically thought to be protected by a layer of tissue that bacteria can’t penetrate, so the results are “unexpected”, says Martin Kriegel, a microbiome researcher at the University of Münster in Germany, who was not involved in the work. “It’s going to be a big paradigm shift,” he adds.

The study was published on 26 February in Cell.

Crumbling dogma

Inherited retinal diseases, such as retinitis pigmentosa, affect about 5.5 million people worldwide. Mutations in the gene Crumbs homolog 1 (CRB1) are a leading cause of these conditions, some of which cause blindness. Previous work2 suggested that bacteria are not as rare in the eyes as ophthalmologists had previously thought, leading the study’s authors to wonder whether bacteria cause retinal disease, says co-author Richard Lee, an ophthalmologist then at the University College London.

CRB1 mutations weaken linkages between cells lining the colon in addition to their long-observed role in weakening the protective barrier around the eye, Lee and his colleagues found. This motivated study co-author Lai Wei, an ophthalmologist at Guangzhou Medical University in China, to produce Crb1-mutant mice with depleted levels of bacteria. These mice did not show evidence of distorted cell layers in the retina, unlike their counterparts with typical gut flora.

Furthermore, treating the mutant mice with antibiotics reduced the damage to their eyes, suggesting that people with CRB1 mutations could benefit from antibiotics or from anti-inflammatory drugs that reduce the effects of bacteria. “If this is a novel mechanism that is treatable, it will transform the lives of many families,” Lee says.

Curb your enthusiasm

Although the paper presents a “cool idea”, people with CRB1 mutations should keep their excitement in check, says Jeremy Kay, a neurobiologist at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. “I’m very concerned that patients are going to read this and think they have an easy answer,” he says, when in fact a complex picture remains.

In the type of mice used in the study, Crb1-associated eye diseases typically take years to fully develop — far outside the time frame of the study — leaving Kay unsure that the results will translate to humans. What’s more, “I don’t believe that they’ve shown that the bacteria really go to the eye extensively enough to do much of anything,” he says. And if gut bacteria are causing eye infections, “you would assume [infections are] happening other places, as well”, which is something that has not yet been observed in people with CRB1 mutations.

“Translation [to humans] is always the big question,” Lee says. Meanwhile, Kriegel says that bacteria translocated from the gut can infect certain other sites preferentially, for reasons that scientists still don’t understand. Because bacteria are rare in the eyes, a small amount could have an outsized effect.

“It couldn’t hurt to try antibiotics in patients,” Kay says. But he also thinks that CRB1 causes genetic changes to the eye that are harmful, even in the absence of bacteria. So, although antibiotics might help with retinal damage, they’re “not going to reverse or cure it”, he says.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-00562-2

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Saima Sidik