The ‘quantum’ principle that says why atoms are as they are

From strange beginnings, the 100-year-old Pauli exclusion principle has become a gift that keeps on giving for scientists who aim to understand the workings of matter

What makes matter stable? Why are atoms as they are? Why do different materials vary in their properties, such as electrical conductivity, density, melting temperature or light-absorption spectra?

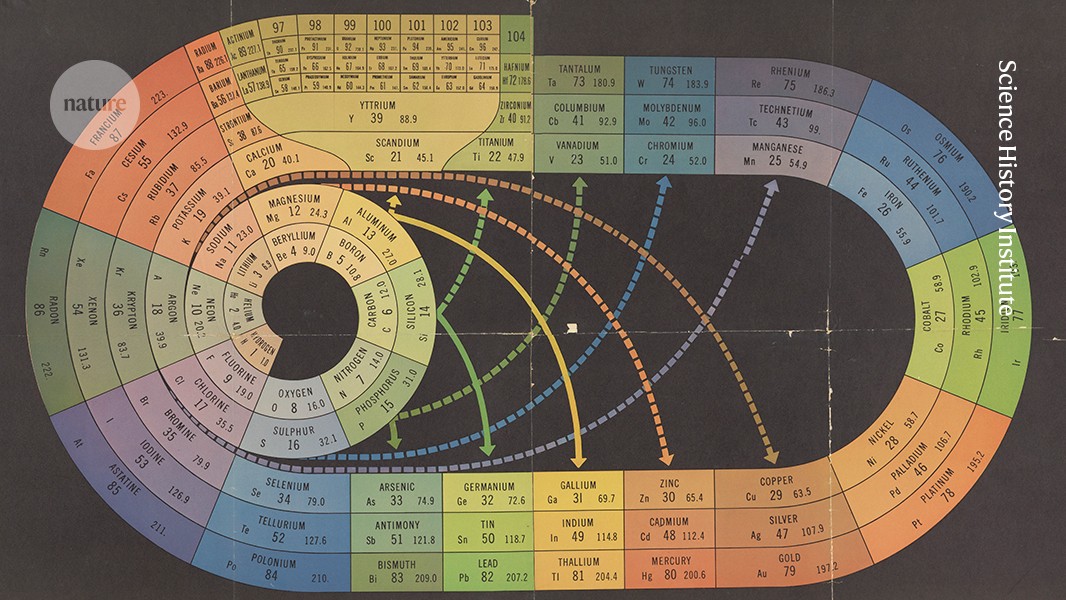

Such questions exercised physicists greatly in the decades after Dmitri Mendeleev introduced his periodic table of the chemical elements in 1869. They received new impetus around the turn of the twentieth century with J. J. Thomson’s discovery that atoms were not indivisible, but contained smaller, negatively charged entities called electrons — the first subatomic particles to be identified. Then, in 1911, came Ernest Rutherford’s discovery that atoms contain a central ‘nucleus’ of densely packed positive charge.

This opened the door to a thrilling journey of discovery, to understand the rules governing subatomic structures. It reached some form of destination a century ago, at the beginning of 1925, with a principle that has underpinned our ideas of the stability of matter ever since.

This is the Pauli exclusion principle, named for the brilliant young Austrian theoretical physicist who devised it1, Wolfgang Pauli. It was a product of what is now labelled the old quantum theory — a period of ad hoc theorizing between 1900 and 1925 that led to the introduction of a consistent theory of quantum mechanics in 1925–27 by Werner Heisenberg, Pascual Jordan, Max Born, Erwin Schrödinger, Paul Dirac and others. Pauli’s principle can be considered the apex of the old quantum theory and, unusually, survived to be incorporated into the new one. Its centenary is an occasion to remember the odyssey of physicists in attempting to understand, amend and test properties predicted by the periodic table, and how this principle has guided our understanding of matter — and not just the conventional stuff.

Bold hypotheses

The discovery of a charged substructure to atoms, which are neutral overall, created considerable difficulty for pictures of how atoms worked. In 1842, the mathematician Samuel Earnshaw showed that there is no stable, static distribution of such charges, ruling out static models of the atom. Yet, despite numerous attempts following the discovery of subatomic structure, no one could arrive at a model that achieved atomic stability and explained features such as the distinct, discrete spectral lines of light emitted by atoms of different elements.

Shortly after Rutherford’s discovery of the nucleus, the Danish physicist Niels Bohr began to attack this problem using quantum principles. He harnessed an idea introduced by Max Planck in 1900 to explain the spectrum of light emitted by a non-reflective ‘black body’ — that energy comes only in discrete chunks, or quanta. Bohr applied it to the spectrum of light emitted and absorbed by hydrogen atoms. The basic hydrogen atom is the simplest of all atoms, now known to consist of a single proton and a single electron.

Bohr started with a picture in which electrons circle the atomic nucleus, rather as planets orbit a star. He postulated that there are specific values of orbital energies at which electrons do not radiate and, therefore, atoms remain stable. Light can be emitted and absorbed only at frequencies corresponding to the difference in energy between two of these stable orbits, which Bohr characterized with different values of a first, ‘principal’ quantum number2.

This bold hypothesis could explain some features of the hydrogen spectrum, but not all. Bohr’s odyssey continued, incorporating new spectroscopic data and theoretical conjectures. These were derived in part from classical mechanics, from applying the precepts of Albert Einstein’s 1905 special theory of relativity to atomic electrons, and by introducing more quantum ideas entirely at odds with classical physics. The ‘quantum of action’ introduced by Planck (now known as Planck’s constant, h, whose ‘reduced’ form when divided by 2π, ħ, is widely used), for example, suggests there is a minimum amount of energy a system can exchange. And Bohr’s own principle of correspondence stated that, when the principal quantum number is large, predictions achieved using this mixed theoretical toolkit should approach the results known from classical physics.

These efforts resulted in Bohr introducing two more quantum numbers3: an azimuthal quantum number, which represented the magnitude of the electron’s angular momentum; and the magnetic quantum number, which described the size of its magnetic moment. These additions made sense in Bohr’s picture of the atom: if the electron is moving along a circular orbit around the atomic nucleus, it would have an angular momentum; and as a charged body in circular motion, you would also expect it to have a magnetic moment.

But again, this couldn’t explain all features of the hydrogen spectrum. By 1923–24, the main puzzle was how to explain the Zeeman effect, in which new spectral lines appear when orbiting electrons interact with an external magnetic field. This is the point at which Pauli enters the story.

Electron exclusion

At the turn of 1925, Pauli was just 24 years old. Already a lecturer in theoretical physics at the University of Hamburg, Germany, he was highly regarded by his peers. Since his youth in Vienna, he had been recognized as a mathematics prodigy — a mantle that he did not wear with ease, as is so often the case. He sought help through the new psychoanalysis promulgated by the psychologist Carl Jung, with whom Pauli maintained a lasting intellectual dialogue4. Pauli was a prolific correspondent, and his published letters are an important source for scientists as well as historians.

Wolfgang Pauli delivering a lecture in Copenhagen in 1929.Credit: Gondsmit/CERN/Science Photo Library

Pauli’s principle1 was informed by ideas from Edmund Clifton Stoner, but his approach was original — and unusual — in many senses. For a start, it seemed to be based mainly in numerology, with no direct connection to known physics. Pauli’s key addition to Bohr’s model was a fourth quantum number — one that, unlike Bohr’s, had no analogy with classical physics, and not even any visual representation in space-time. This new quantum number, spin, could have only two values, either +ħ/2 or −ħ/2. Electrons with opposite values of this quantum number would interact differently with an external magnetic field, leading to the splitting of spectral lines seen in the Zeeman effect.

Nowadays, we know that the spin quantum number cannot be interpreted visually: if you try to model an electron as a charged body spinning on its axis, you find its surface would be spinning at a velocity greater than that of light. It is the strongest indication in atomic models of just how bizarre quantum theory is, filled with features that defy classical intuitions.

Pauli did not formulate his exclusion principle on the basis of classical theories or dynamical principles, but stated it as a simple postulate: that no two electrons in an atom can share the same set of four quantum numbers. As characterized by historian John Heilbron, this statement was rather in the style of the biblical Ten Commandments: “It shall be forbidden for more than one electron [in the same atom] … to have the same values of [all applicable] quantum numbers”5. In this regard, Pauli anticipated the new quantum mechanics, which also — to the distress of many physicists, including Schrödinger and Einstein — abandoned intuitive visual models in the construction of the theory or in its interpretation.

Enjoying our latest content?

Login or create an account to continue

- Access the most recent journalism from Nature's award-winning team

- Explore the latest features & opinion covering groundbreaking research

or

Sign in or create an accountNature 639, 296-299 (2025)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-00731-x

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Olival Freire Jr