India and climate: what does the world’s most populous nation want from COP28? It is also massively dependent on coal

India wants to be the voice of the global south at the climate conference

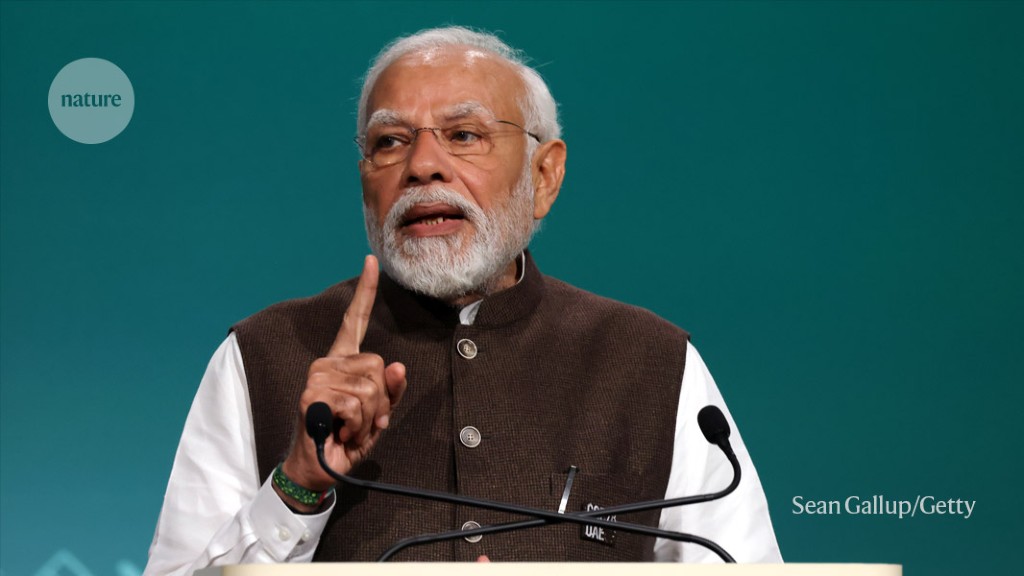

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressed delegates on the first day of the COP28 climate meeting.Credit: Sean Gallup/Getty

India is pitching itself as a leader of the global south at the 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28), under way in Dubai. During his opening speech at the meeting, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi issued a sharp rebuke to wealthy nations: “A small section of mankind has exploited nature indiscriminately. But the whole of humanity is paying its price, especially the residents of the global south.”

But India — now the world’s most populous nation — relies heavily on coal to meet its energy needs, and faces a difficult path to cutting its emissions to net zero. The country’s priority remains reducing poverty — which India says requires more energy use — but more action on climate change is essential, say researchers.

“If we have to reach net-zero by 2050 collectively, then India’s share in that collective goal should be a significant one,” says Nandini Das, a climate researcher based in Perth, Australia, who works for the global research group Climate Action Tracker. But she adds that in terms of finance, “India requires substantial international support”.

New coal

India is the world’s third biggest carbon producer, accounting for 7.3% of global greenhouse-gas emissions in 2022. But those emissions come from 1.43 billion people, accounting for 18% of the world’s population. India’s per capita emissions last year were equivalent to 2.76 tonnes of carbon dioxide, less than one-sixth of the per capita emissions of the United States and 24 times smaller than the figure for Qatar, the world’s largest per capita emitter.

India’s average standard of living is far below those of the United States and Qatar, with 210 million people living in poverty according to United Nations metrics. India has maintained that coal — a cheap fossil fuel readily available in the country — is required to power its economic development. Coal supplied 73% of India’s electricity in 2022; and in November this year, the country announced that it would install 80 gigawatts of new coal-fired power-generation capacity by 2032. “We have to give a fair share to all developing countries in the global carbon budget,” Modi said at COP28.

Parts of India experienced a deadly heatwave earlier this year.Credit: Rajesh Kumar Singh/AP via Alamy

At the conference, India has not signed any declarations that mention decarbonization, including the Global Renewables and Energy Efficiency Pledge, which aims to triple renewable-energy generation capacity by 2030 and calls for an end to new investments in coal. India also rejected a declaration that calls for emissions cuts in the health sector. That’s despite the country having signed a similar renewable-energy pledge and a commitment to develop low-carbon health systems at the meeting of the G20 group of nations in August.

Refusing to sign is part of India’s COP strategy, says Anjal Prakash, a climate-policy researcher at the Indian School of Business in Hyderabad. He says India sees COP negotiations as biased towards rich economies and is taking aggressive steps to safeguard its interests. “India would not sign an agreement for decarbonization at COP unless [wealthy nations] first show that they can decarbonize,” he says.

He says low- and middle-income nations of the global south — countries that have low or historically low emissions per capita and will be worst affected by climate change — see it as unfair to impose on all nations the same 2050 deadline for achieving net-zero as historically high emitters such as the United States. “India is taking leadership for the nations of the global south who are not finding a voice due to the structural problems of the COP system,” Prakash says.

New renewables

For all its expansion of coal, India is also investing in decarbonization steps at home.The nation plans to increase the share of its electricity that is produced by solar and wind power to 35% by 2032, up from 10.6% in 2022. And it aims to increase the share of its generation capacity attributable to non-fossil-fuel power (including hydroelectricity) from 43% to 50% by 2030, according to its submission to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

If India’s UNFCCC pledges are met, and the country continues to accelerate renewable-energy deployment, its carbon dioxide emissions will slow and peak in the 2030s, according to a best-case scenario modelled by the non-profit group Climate Analytics, based in Berlin.

India’s domestic goals are in line with its self-imposed 2070 deadline for reaching net-zero emissions, says Vaibhav Chaturvedi, a researcher with the Council on Energy, Environment and Water, an independent think tank based in New Delhi. “There is no backsliding happening,” he says, although he warns that India’s net-zero trajectory can be properly evaluated only after its emissions peak.

Metrics mismatch

Like other countries with emerging economies, India measures its climate actions using emissions intensity, which is the amount of emissions per unit of gross domestic product. It aims to cut its emissions intensity by 45% below 2005 levels by 2030.

The country is unlikely to switch to using the metric of total emission reductions — known as absolute emissions — soon, because that would require it to phase out fossil fuels.

Chaturvedi says that India will not consider talking about absolute emissions until its economic growth tapers off. “That will happen only once India actually ends up becoming a high-income economy,” he says. “For any developing economy, we cannot say that we are reducing emissions and harming developmental concerns and progress in our own country in favour of the developed world, which will be reaping the benefits.”

Meanwhile, the most climate-vulnerable countries helped push global leaders to adopt a landmark agreement on a loss and damage fund. The fund aims to provide compensation to the low-income countries that are bearing the brunt of climate-change damage.

At COP28, low- and middle-income nations including India are focusing on clarifying how the fund will be handled so that money can be disbursed quickly. “The big expectation and hope is that we should not drag our feet for another five or ten years,” Chaturvedi says.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-03866-x

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Gayathri Vaidyanathan