How our love of pets grew from a clash of world views

Indigenous Americans’ relationships with and knowledge of animals have influenced how Europeans have thought about animals since 1492

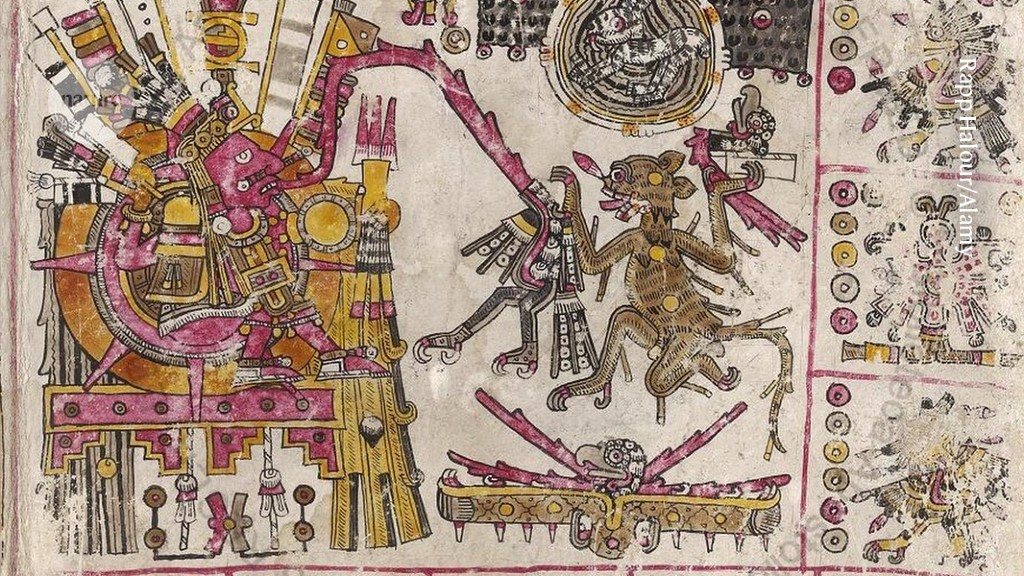

Indigenous peoples of the Americas saw all animals, including humans, as interconnected.Credit: Rapp Halour/Alamy

The Tame and the Wild: People and Animals after 1492 Marcy Norton Harvard Univ. Press (2024)

It’s an enduring myth that the development of livestock husbandry is an essential step on the path of human progress. Many books have emphasized its importance, including historian Alfred W. Crosby’s Columbian Exchange (1972) and geographer Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel (1997). But not all cultures have seen animals as creatures to be penned and farmed. Indigenous peoples in the Americas, for example, recognized that humans and animals have much in common. The clash between differing views of human–animal relationships still resonates today.

In The Tame and the Wild, historian Marcy Norton explores the history and lasting importance of this clash, which began in the late fifteenth century when Europeans arrived on the shores of the Americas, including in the Caribbean. Norton draws on a rich array of sources, including treatises on hunting and natural history, Indigenous books (known as amoxtli), accounts from soldiers and missionaries, trial records from the Spanish Inquisition, dictionaries and paintings. Her fascinating and scholarly account reveals how these encounters transformed Europe and the Americas.

Relationships between humans and animals that emerged from these meetings of different peoples planted the seeds of many of today’s ethical and environmental challenges — from colonial wealth and the dispossession of Indigenous peoples to the modern meat industry. They even explain people’s bonds with their pets.

Food and fear

Norton analyses human–animal relationships in Europe, Greater Amazonia (the Caribbean and lowland South America) and Mesoamerica. Many Indigenous peoples of the Americas consider all beings to be interconnected and permeable. By attempting to think like the animals they hunted, and by wearing the creatures’ pelts and consuming the meat, Indigenous people could take on some of the “beauty and power” of these living beings. By contrast, in Judeo-Christian thought, humans are distinct from and superior to animals.

Norton identifies four ways in which people interacted with animals. In Europe, through hunting and husbandry, and in the Americas, through predation and ‘familiarization’ — a process of feeding and taming individual animals that came and went freely. Familiarized animals were never eaten in Greater Amazonia, but were sometimes consumed during Mesoamerican rituals. Each way of life shaped how people categorized animals and the extent to which animals were considered “fellow subjects with desires, emotions, and even reason”.

In Europe, hunters distinguished vassal animals, such as hunting dogs, horses and falcons, from prey animals, particularly deer and boar. Nonetheless, for a hunt to be successful, hunters had to recognize that their prey had minds with needs, feelings, experiences and motives. Killing prey animals did not require their objectification. But the Christian view of a human–animal divide did provide a basis for livestock husbandry, a practice that requires animals to be seen merely as objects.

Animal features, such as horns, were associated with the Devil in the fifteenth century.Credit: Alamy

The importance of husbandry went beyond nutrition, livelihoods and products, such as clothing. By objectifying animals, people created a “distance between those who owned and managed living animals and those who taxed and consumed their corpses”. With the rise of slaughterhouses — separate from butcher’s shops and required to be outside city limits — consumers in the fifteenth century were disconnected from animal rearing and killing.

But Europeans weren’t able to distance themselves entirely from livestock husbandry during the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. The suspicion that animals might have thoughts and feelings beyond those of hunger or sleep found an outlet in fears about devils and witchcraft. Theologians and inquisitors associated animal features, such as horns, hooves, claws and tails, with the Devil and his human servants, witches. Paintings of Hell depicted the carnage associated with livestock husbandry: reptilian demons led people to slaughter or cut their victims up before roasting them on a spit or boiling them in a cauldron.

Witches were considered to have unnaturally close relationships with animals, to engage in bestiality and to have powers — such as the ability to fly — associated with animals. Well into the seventeenth century, people who had caring relationships with animals that did not have a ‘job’ raised suspicions of witchcraft. Such suspicions led to the execution of some 50,000 people in Europe between the late fifteenth and late eighteenth century.

Missionaries, some of whom had persecuted alleged witches in Spain, carried “their predisposition to see idolaters as shape-shifting sorcerers” to Mesoamerica. Faced with what they saw as an idolatrous culture that “did not uphold a species divide”, they interpreted ritual specialists or “knowledge manipulators” as witches. In so doing, they invented the colonial concept of the nahual, or animal double, out of the Indigenous concept of the nahualli, or knowledge manipulator. Colonial inquisitors tried Indigenous people suspected of having an animal form as sorcerers.

Global links

In contrast to Christians, the peoples of Greater Amazonia understood personhood as something that everything from rocks to humans possessed. Predation transformed prey and predator: people’s bodies were changed by assimilating what they ate, or by what they absorbed from the skins they prepared and wore. Even poison on arrow tips had “vegetative agency”. People had emotional bonds with animals that didn’t require those animals to perform a service. Individual animals were tamed from the wild, not produced through breeding regimes.

Norton argues that “the emergence of the modern pet was, at least in part, a result of this entanglement of European and Indigenous modes of interaction”. In the sixteenth century, most animals shipped to Europe were those that Indigenous people had familiarized. For example, the peoples of the Caribbean Islands and lowland Brazil offered parrots and monkeys to Europeans as gifts and trades — in an attempt to “familiarize” these strangers.

Aristocrats in Europe initially acquired these animals as status symbols. These tame animals transferred the nurturing they had received to their new human companions, who were surprised to find that such relationships were meaningful and desirable.

Norton’s findings contribute to work in the history of science that reveals how modern science — popularly assumed to be Western in origin — has global roots. It was not just discussions with Indigenous peoples of the Americas that European naturalists absorbed into their zoological treatises, but also concepts and practices derived from Indigenous modes of relating to non-human animals.

Norton’s analysis also re-configures histories of conquest. Scholars of Atlantic-Ocean-facing regions of Africa, the Americas and Europe have revealed how Spanish conquistadors joined inter-ethnic conflicts rather than defeating empires such as that of the Aztecs with their bugs, bullets and bigotry alone. As Norton highlights, conquistadors’ expansive use of livestock husbandry “deprived Indigenous people of their labor, their land, and, not infrequently, their lives”. Mines required workers and livestock, and animal husbandry became an alternative industry when mines were exhausted. On the island of Hispaniola, ranchers exported livestock — raised by people held in slavery and Indigenous labourers dispossessed of their lands and coerced into the work — to other colonies in exchange for enslaved people and commodities.

The Tame and the Wild is a meticulous and profound reckoning with human–animal relationships. Illuminating for anthropologists, ecologists, biologists and historians alike, it should be read as widely as The Raw and the Cooked (1964), French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss’s classic study of the myths and world views of peoples of eastern Brazil — whose culinary habits are alluded to in the title.

Nature 626, 945-947 (2024)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-00541-7

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Surekha Davies