How to trick the immune system into attacking tumours

Lab-grown viruses make cancer cells resemble pig tissue, provoking an organ-rejection response

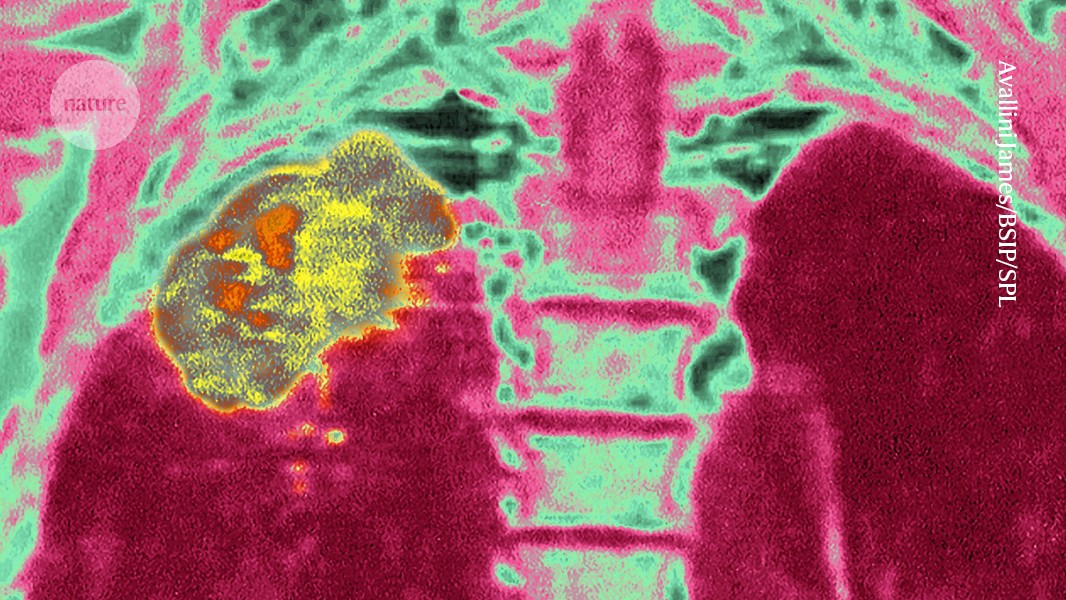

A tumour (yellow; artificially coloured) grows in a person’s lung.Credit: Avallini James/BSIP/Science Photo Library

Scientists have disguised tumours to ‘look’ similar to pig organs ― tricking the immune system into attacking the cancerous cells. This ruse can halt a tumour’s growth or even eliminate it altogether, data from monkeys and humans suggest. But scientists say that further testing is needed before the technique’s true efficacy becomes clear.

It’s “early days” for this novel approach, says immuno-oncologist Brian Lichty at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada. “I hope it stands up to further clinical testing!” he adds. The work is described today in Cell1.

Viral trickery

To devise a strategy against cancer, the authors took a cue from a challenge facing people who receive organ transplants: the human immune system recognizes transplanted organs as foreign objects and tries to eliminate them.

This challenge is especially acute for transplanted pig organs, which could supplement the supply of donated human livers, kidneys and more. But human antibodies immediately attach to sugars that stud the surfaces of pig cells, leading to rapid rejection of the transplanted tissue. (Pig organs transplanted into humans are bioengineered to forestall the antibody response.)

Immunologist and surgeon Yongxiang Zhao at Guangxi Medical University in Nanning, China, wondered whether he could harness this runaway immune response and direct it against tumours.

To do so, Zhao and his colleagues combined lessons from transplant medicine with an anti-cancer strategy called oncolytic virotherapy, which has been around for decades, Litchy says. This approach harnesses viruses to either attack cancer cells or provoke the immune system into doing so.

Co-opting a poultry pathogen

For this therapy, Zhao’s team chose Newcastle disease virus, which can be fatal to birds, but causes only mild disease or none at all in humans. Applied to tumours on its own, the virus fails to elicit an immune response that is strong enough to be helpful clinically. So the team engineered Newcastle disease viruses to carry the genetic instructions for an enzyme called α 1,3-galactotransferase. This enzyme decorates cells with certain pig sugars — the very ones that provoke a fierce antibody attack in humans who receive a pig-organ transplant.

The researchers first tested the therapy in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). Five monkeys with liver cancer that received only saline died an average of four months after treatment. But five monkeys with cancer that received the enzyme-encoding virus survived for more than six months.

The researchers then tested the enzyme-encoding virus in 23 people who had a variety of treatment-resistant cancers, including those of the liver, oesophagus, rectum, ovaries, lung, breast, skin and cervix. Results were mixed. After two years, two people’s tumours had shrunk, but had not completely disappeared. Five people’s tumours had stopped growing. Other participants’ tumours stopped growing but then began expanding again. Only two participants did not receive any benefit from the treatment, although two other people dropped out of the trial before the end of the first year.

Enjoying our latest content?

Login or create an account to continue

- Access the most recent journalism from Nature's award-winning team

- Explore the latest features & opinion covering groundbreaking research

or

Sign in or create an accountdoi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-00126-y

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Saima Sidik