One-quarter of unresponsive people with brain injuries are conscious

More people than we thought who are in comas or similar states can hear what is happening around them, a study shows

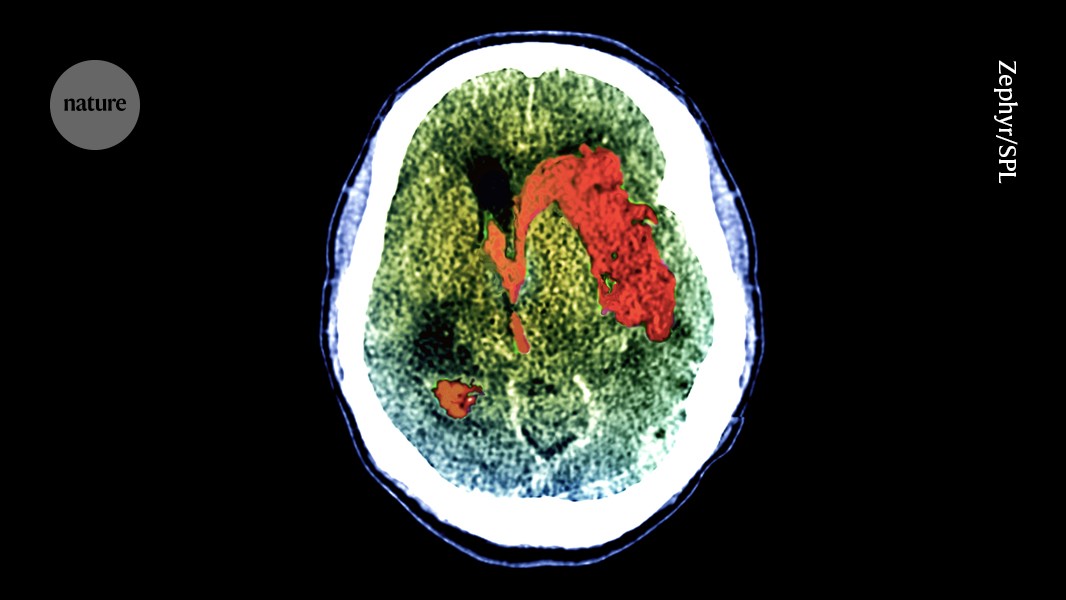

Blood (red; artificially coloured) pools in the brain of a person who has had a stroke, a common cause of coma.Credit: Zephyr/Science Photo Library

At least one-quarter of people who have severe brain injuries and cannot respond physically to commands are actually conscious, according to the first international study of its kind1.

Although these people could not, say, give a thumbs-up when prompted, they nevertheless repeatedly showed brain activity when asked to imagine themselves moving or exercising.

“This is one of the very big landmark studies” in the field of coma and other consciousness disorders, says Daniel Kondziella, a neurologist at Rigshospitalet, the teaching hospital for Copenhagen University.

The results mean that a substantial number of people with brain injuries who seem unresponsive can hear things going on around them and might even be able to use brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) to communicate, says study leader Nicholas Schiff, a neurologist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City. BCIs are devices implanted into a person’s head that capture brain activity, decode it and translate it into commands that can, for instance, move a computer cursor. “We should be allocating resources to go out and find these people and help them,” Schiff says. The work was published today in The New England Journal of Medicine1.

Scanning the brain

The study included 353 people with brain injuries caused by events such as physical trauma, heart attacks or strokes. Of these, 241 could not react to any of a battery of standard bedside tests for responsiveness, including one that asks for a thumbs-up; the other 112 could.

Everyone enrolled in the study underwent one or both of two types of brain scan. The first was functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which measures mental activity indirectly by detecting the oxygenation of blood in the brain. The second was electroencephalography (EEG), which uses an electrode-covered cap on a person’s scalp to measure brain-wave activity directly. During each scan, people were told to imagine themselves playing tennis or opening and closing their hand. The commands were repeated continuously for 15–30 seconds, then there was a pause; the exercise was then repeated for six to eight command sessions.

Of the physically unresponsive people, about 25% showed brain activity across the entire exam for either EEG or fMRI. The medical name for being able to respond mentally but not physically is cognitive motor dissociation. The 112 people in the study who were classified as responsive did a bit better on the brain-activity tests, but not much: only about 38% showed consistent activity. This is probably because the tests set a high bar, Schiff says. “I’ve been in the MRI, and I’ve done this experiment, and it’s hard,” he adds.

This isn’t the first time a study has found cognitive motor dissociation in people with brain injuries who were physically unresponsive. For instance, in a 2019 paper, 15% of the 104 people undergoing testing displayed this behaviour2. The latest study, however, is larger and is the first multicentre investigation of its kind. Tests were run at six medical facilities in four countries: Belgium, France, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The 25% of unresponsive people who showed brain activity tended to be younger than those who did not, to have injuries that were from physical trauma and to have been living with their injuries for longer than the others. Kondziella cautions that further investigating these links would require repeat assessments of individuals over weeks or months. “We know very little about consciousness-recovery trajectories over time and across different brain injuries,” he says.

Room for improvement

But the study has some limitations. For example, the medical centres did not all use the same number or set of tasks during the EEG or fMRI scans, or the same number of electrodes during EEG sessions, which could skew results.

In the end, however, with such a high bar set for registering brain activity, the study probably underestimates the proportion of physically unresponsive people who are conscious, Schiff says. Kondziella agrees. Rates of cognitive motor dissociation were highest for people tested with both EEG and fMRI, he points out, so if both methods were used with every person in the study, the overall rates might have been even higher.

However, the kinds of test used are logistically and computationally challenging, “which is why really only a handful or so of centres worldwide are able to adopt these techniques”, Kondziella says.

Schiff stresses that it’s important to be able to identify people with brain injuries who seem unresponsive but are conscious. “There are going to be people we can help get out of this condition,” he says, perhaps by using BCIs or other treatments, or simply continuing to provide medical care. Knowing that someone is conscious can change how families and medical teams make decisions about life support and treatment. “It makes a difference every time you find out that somebody is responsive,” he says.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-02614-z

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Julian Nowogrodzki