How provinces and cities can sustain US–China climate cooperation But avenues for joint action still exist

National politics is set to drastically shift in both countries

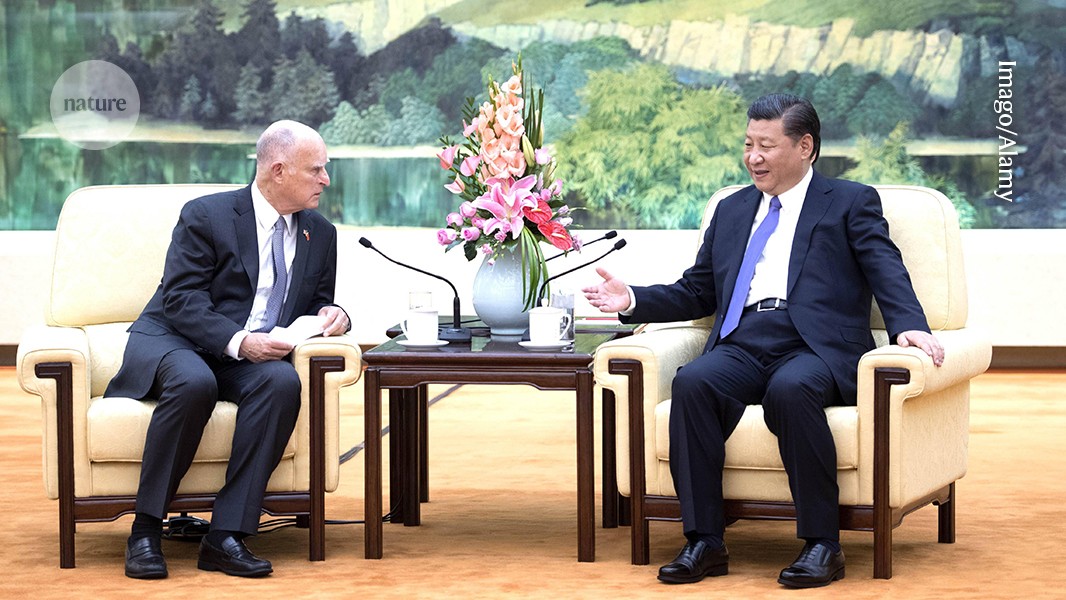

In 2017, the governor of California Jerry Brown (left) met with China’s President Xi Jinping to sign a series of climate agreements.Credit: Imago/Alamy

The relationship between the United States and China stands at a crucial juncture. Given Donald Trump’s recent victory in the US election, the slowdown in China’s economy and rising tensions around trade and technology, productive cooperation between the two countries is far from guaranteed.

President-elect Trump has already indicated that federal policy on climate and environmental issues, among others, might shift drastically. For instance, he has vowed to end offshore wind development on “day one”, halt renewable energy subsidies that were introduced by President Joe Biden under the Inflation Reduction Act and raise tariffs on all imported goods.

If these proposed policy changes take effect under the new administration in January, they will have a pronounced impact on the US–China relationship, which is already fractious. Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that both countries share common vulnerabilities, including weather-related disruption caused by climate change, and have reasons to act jointly in some areas. Indeed, sustained engagement between the world’s two largest economies is crucial for making progress on global challenges.

Fortunately, there are ways of sustaining mutually beneficial action in an era of great power competition. Subnational governments (states, provinces and cities) and non-state actors (businesses, academia, non-profit organizations and philanthropies) can play a crucial part in supporting dialogue and collaboration.

Over the past few years, instead of waiting for clarity on policies from the US federal government, several states have decided to chart their own paths. The Senate Bill 100 in California requires 100% of the state’s electricity to come from renewables by 2045. New York will reduce greenhouse-gas emissions by 40% by 2030 from 1990 levels, through the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act. Other states, such as Washington, have enacted similar legislation to ensure progress on renewable-energy adoption and emissions reductions, even in the face of federal disengagement. These efforts mirror broader state-level initiatives to future-proof policies in areas such as health care and civil rights, positioning subnational jurisdictions at the forefront of climate policy and regulation.

Here we describe joint initiatives between California and Chinese agencies and provinces on clean energy and climate action. We highlight areas in which expanding subnational collaboration can be effective and lay out steps to advance the US–China partnership on climate change. Although national governments might be instinctively wary of subnational cooperation, the benefits, in our opinion, far outweigh any perceived risks.

Open spaces for dialogue

Collaboration between California and China has grown over the past decade, in response to shifts in US federal policies. Climate change was a pillar of the US–China relationship during the administration of president Barack Obama, from 2009 to 20171–3. The Trump administration’s subsequent retreat from the 2015 Paris climate agreement and its disengagement with China created a void. California stepped in to help fill it.

In 2017, the then governor of California (one of us, J.B.) met with China’s President Xi Jinping and signed a series of climate and energy-focused agreements between California and several of China’s national agencies and provincial governments. These strengthened earlier ties and built on California’s first memorandum of understanding (MOU) on climate change with China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and Guangdong and Jiangsu provinces, which was signed in 2013.

When Biden’s administration entered office in 2021, the United States rejoined the Paris agreement. Both countries put forward envoys — John Kerry, the former US secretary of state, and one of us (Z.X) — to aid dialogue and cooperation around climate change. Discussions between the envoys paved the way for a meeting in November 2023 between presidents Biden and Xi during the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) conference held just outside San Francisco, California.

Afterwards, the two countries released a joint statement on enhancing cooperation to address the climate crisis. They identified areas for deeper bilateral collaboration including exchanging know-how on the transition from coal to green energy, methane emissions reductions and waste reduction through more efficient uses of resources.

After the summit, working groups were set up to exchange ideas in each of those domains. Discussions from these groups culminated in a high-level bilateral meeting at the California–China Climate Institute (CCCI) in Berkeley, California, in May this year; participants included the governors of California and the Guangdong province and officials from five cities and four provinces of China4. Specialist groups are now being set up to provide technical support for implementing a joint agenda in areas such as energy decarbonization.

The United States can learn from China’s expertise in offshore wind technology.Credit: Kendall Warner/The Virginian-Pilot/Tribune News Service via Getty

By implementing its commitments to reduce carbon emissions in coordination with Chinese counterparts through region-to-region technical exchange and local pilot programmes, California has shown what’s possible when subnational jurisdictions take the lead and set an example. Other US states looking to enhance their international engagement now have a template.

Although China has a formal mechanism — the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries — to foster relationships with provinces and cities of other countries, the partnership with California is unique because it has signed MOUs with China’s central agencies, such as the NDRC.

The reason why the two sides see great value in such cross-border cooperation can be illustrated through one example. As California gears up for the rapid deployment of offshore-wind projects, few organizations in the United States have the relevant expertise to offer guidance on installing these turbines in ways that minimize their impact on marine habitats. That’s why the state has engaged in continuing dialogue with several Chinese wind-turbine manufacturers.

Meanwhile, China has modelled its new green building regulations after California’s Title 24 standards — a set of building codes that ensure energy efficiency. Beijing’s air-quality management policy has also been informed by existing mechanisms in California. But there is room to broaden these areas of mutual benefit into unexplored domains. Here are three priority areas.

Decarbonizing technologies

Many states and provinces in the United States and China are facing similar challenges in decarbonizing their economies. For example, Guangdong in southern China, which is adjacent to Hong Kong, has much in common with California both geographically and economically.

Exchanging technology and policy knowledge could benefit both regions, which are hubs for talent, technology and capital. California offers expertise in emission-reduction strategies and climate-resilient infrastructure, which are relevant to cities in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA). Chinese cities in this area have developed expertise over the past two decades in high-speed rail, a low-emission alternative to road and air travel. They also have expertise in the deployment of offshore wind technology, an area of continuing collaboration in which engagement could be deepened.

Between 2010 and 2022, the share of electricity generated by renewables in California shot up from 15% to 36% owing to the state’s targeted policies and incentives for clean energy5. Meanwhile, China’s Qinghai province, which is on the Tibetan Plateau, operated its power grid with more than 85% clean energy — mainly solar and hydro power — in 2023. The province’s successful model for renewable integration makes it a valuable partner for California to explore zero-carbon strategies (see go.nature.com/3z3addm).

However, the potential benefits of provincial collaboration are not confined to technologically advanced regions. For instance, coal-producing US states, such as Colorado, have engaged in discussions with China’s coal-reliant regions, such as the northern autonomous region of Inner Mongolia, since 2023 to initiate their transition to clean energy.

Electricity grids and markets

Operating the power grid using clean-energy sources is tricky because wind and solar power is available intermittently, making it harder to match supply and demand in real time. And China’s clean-energy push faces a further obstacle: solar and hydro power produced in the sparsely populated interior regions must be transmitted over thousands of kilometres towards big cities such as Shanghai and Beijing.

Overcoming those hurdles requires improvements in the power grid, including extra energy storage and well-functioning electricity markets, which can match suppliers with consumer demand in real time. In most countries, peak power consumption occurs during the evening hours, whereas solar plants are best placed to produce power in the middle of the day. Since the period of peak supply — which is dependent on sunlight and wind — and demand do not overlap, electricity markets and dynamic pricing are necessary to nudge producers and consumers towards an equilibrium. For example, if consumers must pay a higher price when the availability of solar energy is low, they might change their daily behaviours and, at the aggregate level, balancing the grid would become easier.

Currently, power contracts in China are put in place through top-down mandates, in which a government agency determines the unit cost of electricity. Spot electricity markets, in which prices are determined in real time on the basis of demand, are almost unheard of. The United States, however, has considerable experience with managing and regulating market-based mechanisms. By sharing expertise, the United States and China can help one another to address their challenges.

Climate finance

Billions of dollars in investment are required over the next decade in California and the GBA of China to drive research and build clean-energy capacity. Following the subnational meeting in May, another MOU was signed between the two regions to expand dialogue on carbon-market development and climate finance.

Carbon markets raise funds through the sale of carbon credits, which companies purchase to offset their emissions. Climate finance vehicles, meanwhile, are investment structures that raise and allocate capital for climate-related projects and sustainable development goals. In effect, both are mechanisms to direct private capital towards initiatives intended to mitigate climate change. If major cities in California and China decide to raise capital by jointly floating green investments, the odds of success are higher. Risks and resources will be shared, and as a result, private investors will have greater confidence in securing a good return on their investments.

US states that wish to activate such cross-border market development mechanisms must start by aligning policies — such as having common guidelines for what can be categorized as a climate-friendly project, for instance. Providing adequate training to local and regional government employees so that they can set up and operate such financial vehicles is also important. Ultimately, a strategic focus is required to mobilize greater resources at the subnational level, which states can then use to push forwards their unique local agenda.

Next steps

Although developments over the past four years represent some success in the US–China climate partnership, the road ahead is still rocky. Given the evolving political landscape, we recommend four steps to help scale and enrich this climate-centred partnership.

Support subnational cooperation. The realities of a strained US–China relationship necessitates a shift from conventional top-down bilateral diplomacy to a multilayered (involving government and non-state actors) and multidirectional (top-down and bottom-up) approach. Both national and local governments need to empower regional initiatives, provide policy frameworks for cooperation and fund joint projects that enable sustained cross-border efforts even in challenging diplomatic periods.

Broaden participation. So far, only a small subset of states, provinces, cities, businesses and universities have participated in climate-related exchanges between the United States and China. Institutions such as the CCCI can initiate outreach to include more states and provinces. Furthermore, intergovernmental organizations can offer coordination platforms to aid meaningful exchanges and policy alignment across regions.

Prioritize what works. In this fresh era of US–China relations, there is still uncertainty about what the best modes of cooperation between the two countries might be — virtual workshops, in-person meetings and site visits, regular policy dialogue, staff exchanges and training. Regular reflection on what’s working and prioritizing those areas in which cooperation is mutually beneficial will be helpful. California’s MOUs and work plans with Beijing, Guangdong, Hainan, Jiangsu and Shanghai provide a test bed to explore different forms of cooperation.

Advance multilateralism. Climate change is a global problem, which means that subnational cooperation must find its way back to the global stage eventually. National governments can support and encourage the participation of subnational governments and businesses in multilateral forums, and these local governments can coordinate their participation and use these forums as an opportunity to build and strengthen longer-term relationships.

Sceptics of subnational cooperation might voice concerns over potential compromises to national sovereignty and the risk of creating technological dependencies. Yet, the pressing reality of climate change demands a shift away from conventional geopolitical frameworks.

Any successful effort to combat climate change depends on the willingness — and enthusiasm — of the United States and China to cooperate. No matter how formidable the obstacles are, collaboration remains the most viable path forwards.

Nature 636, 39-42 (2024)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-03919-9

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Fan Dai