The expanding Universe — do ongoing tensions leave room for new physics?

One century after Edwin Hubble revealed his astonishing discovery of a cosmos beyond the Milky Way, the most precise measurements still can’t agree on how fast galaxies are moving

On 1 January 1925, US astronomer Henry Norris Russell made a startling announcement to the American Astronomical Society in Washington DC: observations by fellow astronomer Edwin Hubble showed that the Milky Way did not encompass the cosmos, and that myriad galaxies exist beyond our own. Hubble’s findings revolutionized humanity’s perspective on the Universe and continue to challenge astronomers even now, one century on.

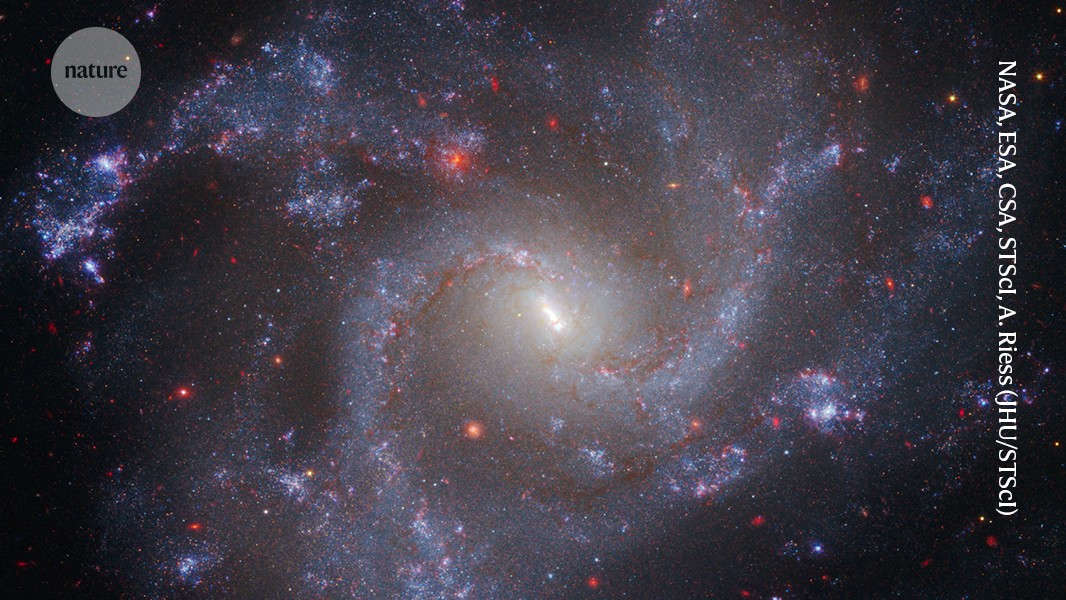

Hubble had gained these insights from a handful of intriguing black dots on glass photographic plates1 — stars of variable brightness known as Cepheids. He had discovered these objects while working at the Mount Wilson observatory near Pasadena, California, including in images of a striking ‘spiral nebula’ in the constellation of Andromeda, a fuzzy object among the stars that looked like a whirlpool. The embedded variable stars proved that the Andromeda nebula was much farther away than the stars that comprised the Milky Way. Andromeda was therefore a separate galaxy — similar to, yet distinct from, our own.

And Andromeda wasn’t alone. The night sky was peppered with hundreds of spiral and irregular-shaped nebulae hiding among the stars. The Milky Way didn’t go on forever; rather the Universe was filled with other galaxies (now known to number in the hundreds of billions). This was just the beginning. Hubble set about searching for Cepheids in these far-away galaxies so that he could pinpoint their distances, too. By 1929, Hubble had noticed a correlation between the galaxies’ distances and the velocities at which they seemed to be receding from Earth.

A few years earlier, astronomer Vesto Slipher had reported a shift to longer (redder) wavelengths of key atomic signatures in the spectra of nebulae, indicating that the objects were travelling away from Earth2. Together with Hubble’s distances, these data implied that more-distant galaxies were moving away faster, suggesting that the Universe must be growing with time3. It was an astounding revelation.

Theoretical physicists had already allowed for this expansion using mathematical models, based on Albert Einstein’s 1915 general theory of relativity4 and calculations by Alexander Friedmann5 and Georges Lemaître6. (Interestingly, Einstein had considered expansion, but dismissed it.) These models — and an emerging understanding of nuclear physics — implied that the Universe had burst forth from the explosion of a dense primeval fireball, and had been expanding and cooling ever since.

Firm evidence supporting this ‘Big Bang’ theory came in 1965 with the discovery of the cosmic microwave background7 — remnant radiation from when the Universe became transparent some 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

Astronomer Fred Hoyle coined the catchy name in a 1949 radio programme, to help explain the phenomenon to the public. Although the term was interpreted by many people as derisive, he later said he did not intend it in that way.

Scientists have since worked hard to pinpoint how fast the Universe is expanding, and how long ago the Big Bang took place. It’s a compelling tale, with lots of twists and turns. But, 100 years on, there’s still much that we don’t know. And there might even be room for some new physics.

Measuring the expansion

The Hubble constant is a measure of the rate at which the Universe is currently expanding. From his measurements3, Hubble derived an initial value of around 500 kilometres per second per megaparsec (where 1 parsec is 3.26 light years). In other words, for each megaparsec a galaxy lies farther away, we see it receding 500 kilometres per second faster.

Extrapolating that back in time, the Universe must have been ever smaller and denser. Thus, the expansion rate can tell us how old the Universe is — how long it has been expanding for. And Hubble initially projected that the cosmos was just two billion years old. However, that didn’t make sense, because at the time, radioactive dating of the oldest known rocks on Earth suggested that they were at least three billion to four billion years old. Earth couldn’t have existed longer than the Universe itself.

Astronomers redoubled their efforts to measure the rate of expansion more accurately. By the 1970s, the constant had come down from 500 to between 50 and 100, suggesting that the Universe was roughly 10 billion to 20 billion years old8. That frustrating factor of two, however, remained stubbornly in contention for another 30 years.

Pinning down the constant

Astronomers face formidable challenges when measuring cosmic distances. Hubble relied on Cepheid variables for his measurements — analysing stars that exhibit a cycle of brightening and fading. The more luminous the Cepheid, the longer its pulsation cycle, a relationship discovered by astronomer Henrietta Leavitt9. The rate at which the star pulsates is related to its intrinsic brightness. By comparing this brightness to how bright the star seems, Hubble could calculate its distance.

Unfortunately, the measurement of distances has proved a lot more challenging than was apparent to Hubble. In practice, systematic effects — such as calibration uncertainties in instruments, dimming of distant stars by intervening interstellar dust grains, differences in the chemical compositions of stars, our inability to resolve individual stars when they are clustered and small sample sizes — are a persistent obstacle.

Edwin Hubble’s annotated plate of the Andromeda galaxy.Credit: Courtesy of Carnegie Science

Several pieces of the cosmological puzzle fell into place around the turn of the twenty-first century. Digital detectors had replaced photographic plates, improving precision. Innovative methods were developed to correct for the effects of dust. Importantly, the launch of the Hubble Space Telescope in 1990 and a key project to measure the Hubble constant — which I led — enabled observations of hundreds of Cepheids in 24 distant galaxies with 10 times the resolution of Earth-based telescopes.

These advances narrowed the value of the Hubble constant markedly10, to a value of 72 with a precision of 10% — finally resolving the long-standing ‘factor of two debate’ in the distance scale. But solving one problem merely revealed another. When a value of 72 was input into the most up-to-date cosmological models of the time, it implied that the Universe had existed for just 9 billion years. However, by this point, astronomers had measured that the oldest stars in the Milky Way were at least 12 billion years old.

A striking discovery in 1998 — that the expansion of the Universe was not steady but accelerating — potentially offered a way out of this unwelcome crisis. This cosmic acceleration is driven by what astronomers now refer to as ‘dark energy’, a repulsive form of gravity that is allowed by Einstein’s general theory of relativity. A Universe that is accelerating wouldn’t always have been expanding as fast as it is today. The presence of dark energy allows for the Universe to be older, and even for its age to be consistent with that of stars in the Milky Way. But, still, there were more puzzles to solve.

Short-lived consensus

Measuring distances to galaxies is just one way of judging the expansion rate of the Universe. In 2001, a satellite was launched that provided a new and independent means of estimating the Hubble constant. NASA’s Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP)11 measured tiny differences across the sky in the temperature of the cosmic microwave background, at the level of a few parts in 100,000. By comparing these differences to cosmological models, the expansion rate could be deduced.

By then, cosmological models had incorporated several exotic ingredients. As well as dark energy, there had previously arisen strong evidence for the presence of ‘cold dark matter’, a form of matter that is currently thought to comprise as-yet-unidentified particles produced in the Big Bang. This dark matter does not emit or absorb light, but does interact gravitationally with the ordinary, visible matter that makes up the Universe’s luminous components, including stars and planets.

Overall, ordinary matter makes up only 5% of the cosmos. Dark energy dominates the overall mass-energy density of the Universe, comprising 68% of the total12, and dark matter contributes the remaining 27%.

Fitting the WMAP data led to a value of 71 for the Hubble constant — very close to the estimate of 72 based on Hubble Space Telescope Cepheid data. But this comforting consensus in cosmology was short-lived.

In 2009, the European Space Agency launched a satellite, called Planck, that had a greater sensitivity than did WMAP, to measure the cosmic microwave background. In 2013, the Planck collaboration announced its first results13, including a Hubble-constant value that was markedly lower than that found using Cepheids: 67.3, with a precision of better than 2%. In 2018, this was sharpened to a value12 of 67.4 ± 0.5, indicating a precision better than 1%.

Enjoying our latest content?

Login or create an account to continue

- Access the most recent journalism from Nature's award-winning team

- Explore the latest features & opinion covering groundbreaking research

or

Sign in or create an accountNature 639, 858-860 (2025)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-00896-5

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Wendy Freedman