Six roadblocks to net zero — and how to get around them

Overcoming these obstacles in carbon markets can speed up decarbonization

Net zero. This simple accounting term represents humanity’s greatest challenge — and opportunity — to stabilize Earth’s climate. The goal, timeline and metric for success seem clear: by 2050, each tonne of carbon emitted must be matched by a tonne removed. But achieving this is easier said than done.

Since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, the world has built up more than 250 years of momentum in a carbon-emitting economic and technological paradigm. Now, under the terms of the 2015 Paris climate agreement, it has just 25 years — or a few business cycles — to replace the carbon-dependent parts with net-zero components.

The journey requires unprecedented coordination, innovation, investment and speed to avoid the catastrophic consequences of failure — including increasingly severe natural disasters, from rapidly rising sea levels and floods to heatwaves and wildfires. We, the authors, understand the potential and pitfalls, having spent more than 20 years between us developing the strategies, programmes, products and policies that achieving net zero demands.

We have deployed and influenced more than US$1 billion in investments and purchases related to carbon reduction and removal, and have been on the front lines of driving large-scale voluntary decarbonization in the corporate sector. Previously, we served as principal architects of Microsoft’s carbon-negative commitment. Now, one of us (E.W.) is a net-zero strategy consultant, and the other (L.J.) is a private-equity executive working to deliver a net-zero investment portfolio.

Although we have a deep conviction that net zero can work, we know it has issues. A premature desire for perfection, overly precise guidelines for implementation, insufficient flexibility in carbon accounting, unhelpful constraints on collaboration and a disproportionate focus on the actions of others all combine to slow down the net-zero transformation just when it needs to speed up. Here, we describe the barriers and suggest ways to overcome them.

Obstacles to market growth

For net zero to work, the world must design markets in which every product or service, everywhere, prices in the cost of removing carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases from the atmosphere or replacing them with an alternative that emits little or no carbon. Regulation will play a crucial part. But adoption at scale will happen only when removals and low-carbon alternatives are cheaper in price, superior in performance, or both, relative to higher carbon incumbents.

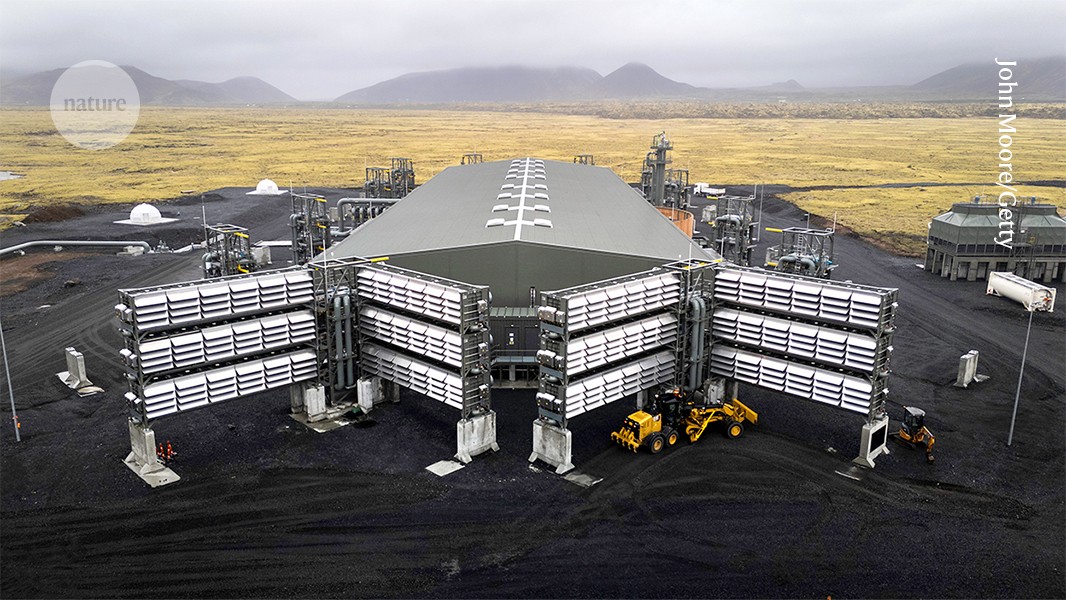

Reduction and removal technologies are still in their infancy. Sustainable aviation fuel, green hydrogen and steel, low-carbon concrete and technologies that capture CO2 from the air are expected to be part of a future net-zero economy. But today, they are too scarce and expensive to enable stakeholders to build anything more than theoretical plans around them.

Long-term cost-efficiencies and supply will emerge only through large investments in a host of approaches, allowing the markets to determine winners and losers. This was a clear lesson from decades of advances in solar and wind energy, which ultimately saw the costs of these renewables plummet by more than 70%.

To meet net-zero goals, global investments in the clean-energy and carbon-removal sectors, and their supporting infrastructure, must exceed $4 trillion annually by 20301. But we are concerned that current carbon-market expectations are inadvertently making it harder — not easier — to deploy the climate capital needed to build robust carbon markets.

Despite widespread agreement on the need for net zero, few binding requirements compel individuals or organizations to act in support of climate goals. This creates a carbon catch-22: governments are hesitant to impose regulations without clear price signals from markets, while markets struggle to deliver price clarity without regulatory guidance.

As a result, achieving net zero globally must rely heavily on early movers — organizations that pursue net-zero outcomes voluntarily. But, so far, there are too few of these, and they aren’t moving quickly enough. In part, that is because the net-zero landscape is dominated by prescriptive rules that are difficult to implement, often creating confusion instead of clarity.

These roadblocks must be removed. Here we identify six remedies.

Pursue progress over perfection

Organizations need flexibility if they are going to commit to innovation. For example, in the early days of renewable energy, corporate buyers purchased renewable energy credits to meet their 100% renewable electricity goals that would not meet quality standards today. But they got the ball rolling: buyers invested, learnt and iterated. Procurement of ‘unbundled’ renewable-energy certificates was replaced by more sophisticated ways of buying and selling energy, such as through contracts to match hourly energy consumption.

A carbon-transport ship in Norway takes waste carbon dioxide from industrial processes to a storage facility near Bergen.Credit: Carina Johansen/Bloomberg via Getty

Similarly, today’s corporate leaders are advancing energy projects on a voluntary basis, from nuclear to geothermal. Their energy prices are high now, but will come down if buyers and suppliers are given room to improve the technologies. In other words, setting an ambitious but achievable goal and sticking with it, while continuously improving its execution, should be a core principle for reaching net zero.

Yet, rigid and complex standards introduced too soon are discouraging companies from innovating. For example, last year, the Science Based Target Initiative (SBTi) removed nearly 240 companies — representing more than $4 trillion in market capitalization — from its Corporate Net Zero Standard, because of their inability to meet its stringent criteria2. This highly publicized action led to frustration from the affected companies, some of which stated they were unaware that the deadline for meeting these criteria was approaching.

Delisting or penalizing companies for ‘missing’ arbitrary net-zero milestones should be avoided. SBTi’s working groups should recommend that flexibility and iteration are core pillars of its forthcoming revision to the Corporate Net Zero Standard (see go.nature.com/428ukzq).

Prioritize direct over indirect emissions

The Greenhouse Gas Protocol, a partnership between businesses, governments and other organizations that has set global standards for measuring emissions, has established three ‘scopes’ for voluntary reporting of emissions by corporations. Scope 1 includes an organization’s direct emissions (such as those from a steel producer’s coal-powered kiln). Scope 2 reflects those associated with consuming electricity, as well as heating and cooling. Scope 3 emissions represent all those embodied in an organization’s supply chain and product-delivery networks. Thus, Scope 2 and Scope 3 emissions help companies to understand the wider carbon implications of their operations. But, if every company reduced their Scope 1 emissions to zero, then every other company’s Scope 2 and Scope 3 emissions would also disappear.

For most companies, Scope 3 captures most of their emissions. Accounting for these has helped to drive a cascade of decarbonization commitments, such as identifying, addressing or replacing high-carbon producers. That is good.

But a disproportionate focus on reporting Scope 3 emissions — including by the SBTi, the CDP (an international non-profit organization dedicated to collecting information on corporate sustainability efforts) and jurisdictions such as the United States and the European Union — has arguably distracted many companies from doing the hard work at home. In 2022, only 7% of consumer companies were on track to meet their targets for value-chain decarbonization, and only 18% were on track with their direct-emissions targets (see go.nature.com/43ystkc). Companies could make more progress on Scope 1 if they were able to simplify and focus their attention.

First, requiring companies to commit to reductions they have little or no control over, and then penalizing them for failing to make progress, discourages them from engaging. Indeed, in a 2024 survey by the SBTi, Scope 3 difficulties were the biggest complaint from companies working on climate issues, mentioned by 54% of firms2.

Second, a focus on Scope 3 introduces extreme uncertainty into reporting of carbon emissions. The most common way to derive Scope 3 emissions is to multiply how much is spent on certain broad categories, such as ‘marketing’, by a numerical factor approximating national or global emissions for that activity. This simplistic approach misses both the accuracy and precision that reporting bodies desire.

And third, Scope 3 emissions can potentially divert focus away from Scope 1 and 2 emissions for a reason of efficiency: if most of an organization’s emissions are indirect, why focus first on the minority that are direct?

The fix is simple. SBTi, CDP, regulators and other parties should create a tiered system that prioritizes target setting and reporting for Scope 1 and 2 over that for Scope 3. Companies should be making progress on decarbonizing their Scope 1 and 2 emissions before they are expected to tackle the more difficult Scope 3.

Focus on demand over delivery

Corporate demand has had an outsized role in developing renewable-energy markets. Starting in the 2010s, companies were motivated to make purchases because they received credit for doing so under the Greenhouse Gas Protocol. But the protocol’s accounting practices contain an inconsistency. Under its ‘location-based’ and ‘market-based’ accounting rules, companies can get credit for Scope 2 carbon reductions from the electricity they consume by purchasing renewable energy that is never physically delivered to them. But there is no mechanism to do that for Scope 1 or 3.

Engineers work on an electrical panel at Octavia Carbon, a carbon-capture plant near Nairobi.Credit: The Washington Post/Getty

The protocol now needs to be expanded to allow for such claims across all emissions classes. It is more important that solutions are contracted and paid for than specifying where and to whom they are delivered. For instance, being able to track the delivery of sustainable aviation fuel to a buyer in a specific seat on a particular aeroplane is less important than ensuring that an equivalent amount of fuel was delivered into the broader aviation network.

Allowing companies to claim credit for these purchases would incentivize them to invest. To build trust, descriptions of the projects funded or financed can help others to assess the value of any company’s carbon reduction and removal purchases.

Allow flexibility between emissions reduction and removal

As the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has emphasized, limiting the worst harms of global warming requires both reduction of emissions and large-scale carbon removal. In the context of global net zero, how much reduction is needed versus how much removal is an open question, and well-intentioned but premature mandates hold back innovation.

For example, SBTi’s Corporate Net Zero Standard requires a company’s decarbonization commitment to include a pledge to reduce their emissions by 90% or more before relying on carbon-removal technologies to counterbalance the remaining 10%. This requirement is too strict, and too early.

By analogy, in the renewable-energy sector, early markets were unconstrained by requirements for specific amounts of solar, wind or hydropower. Instead, technologies competed, and winners emerged for different uses in different places. A market-driven approach allowed the most effective solutions to materialize naturally over time.

Enjoying our latest content?

Login or create an account to continue

- Access the most recent journalism from Nature's award-winning team

- Explore the latest features & opinion covering groundbreaking research

or

Sign in or create an accountNature 640, 31-34 (2025)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-00935-1

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Lucas Joppa