Clarity or accuracy — what makes a good scientific image? A revealing book cautions us to look closely at what pictures are really telling us

Photography is not just illustrative, it is investigative

Flashes of Brilliance: The Genius of Early Photography and How It Transformed Art, Science, and History Anika Burgess W. W. Norton (2025)

As someone who has spent a career visualizing science, Flashes of Brilliance felt like reading a love letter to the power of the photographic image. This beautifully written book, by writer and photo editor Anika Burgess, is a thoughtful, personal and witty meditation on how imagery does much more than just document a scene.

Along with fascinating examples of early efforts to capture images of society, the book captures well the dual role of the scientific image — as both a tool for discovery and a medium of communication. A reader begins to understand that photography in general, and especially in science, is not just illustrative, it is investigative. And sometimes, as Burgess clearly describes, it is revelatory.

Through a series of compelling stories and visual examples, the author reminds us that an image can crystallize a complex idea in a way that no string of words ever can. It’s a celebration of ‘aha’ moments made visible. Those photographs wake us up to social issues and phenomena we never even knew existed.

Jacob Riis’ images of the squalid conditions of people living in tenements in New York City’s Lower East Side around 1889 say so much more than any text describing the situation. By using flash powder to add light to the exposure, he could reveal details of these ordinarily gloomy spaces and those inhabiting them.

Jacob Riis captured the poor conditions of people living in New York City around 1900, such as these children sleeping on a steam grate for warmth.Credit: Granger/Historical Picture Archive/Alamy

Manipulating reality

Burgess doesn’t shy away from the challenges, either — acknowledging how easily images can mislead or manipulate. Even from the beginning, some photographers used a technique to combine negatives in the printing process to create unreal scenarios. In the early 1870s, Édouard Buguet used this method to insert a translucent ‘spirit’ above the people in his portraits to advance the idea that the dead could communicate from beyond the grave. Many viewers thought that the spirit was real; only in 1875 did Buguet admit that the images were fake.

The balance between clarity and accuracy is something I’ve grappled with throughout my career, and it’s refreshing to see this issue addressed so directly. These days, at least in science, any manipulation must be considered carefully and reported.

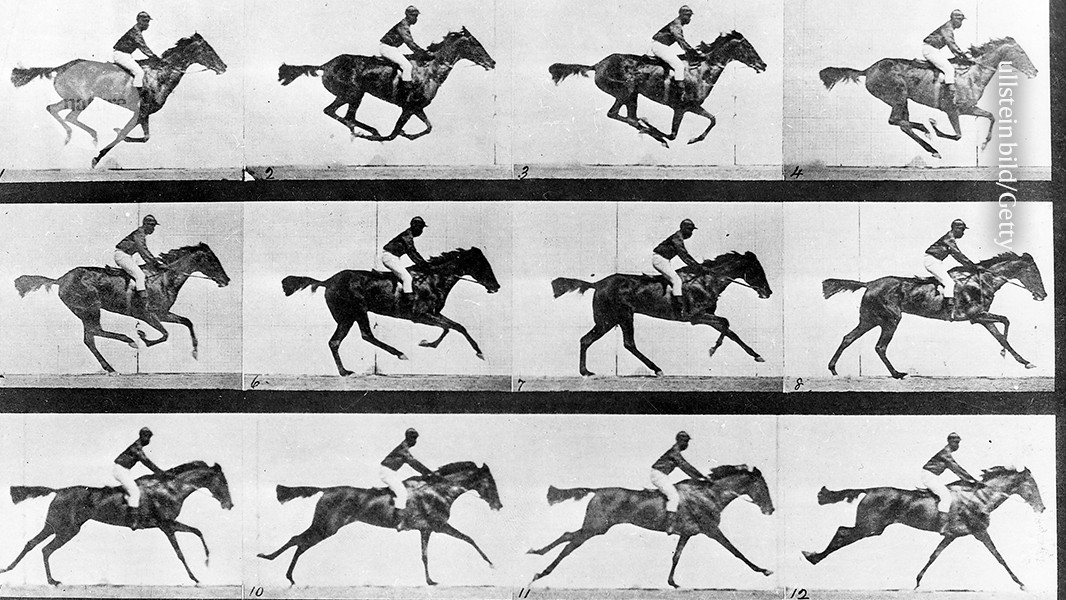

Another example came as a surprise. I never tire of studying Eadweard Muybridge’s beautiful sequences of still images showing horses in motion. His photographs from the late 1870s clearly show that at various moments in a trot, all four horse hooves leave the ground at the same time — a fact that wasn’t known until then. What was new for me was to read how “he substituted, or missed out and renumbered, certain sets of images, which naturally calls into question their scientific utility”. As historian Marta Braun argues in her 1992 book Picturing Time: “under the guise of offering us scientific truth”, Muybridge has “like any artist made a selection and arranged his selection into his own personal truth”.

Craig and George Falconer produced several ‘spirit’ photographs in the 1920s.Credit: Dan Moss/Alamy

For those of us in science communication, this warning is essential. Just because an image is beautiful doesn’t mean it tells the whole story. However, I don’t want to completely discount his contribution to this ‘aha’ moment in science. Informing us of his process (just as NASA scientists do when they colour astronomical images) and why he did what he did would have helped us to consider the study as an authentic scientific investigation.

Although Burgess emphasizes the early years of picture making, I was compelled to compare some of her thinking with writer Susan Sontag’s discussion in On Photography (1977). Sontag famously argued that “to photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed” — these images have allowed our minds to consider whatever we are seeing as reality. And this idea resonates with many of the moments in Flashes of Brilliance in which early image makers were not only documenting the world but transforming it into something permanent, collectible and possible.

Whether it is Cecil Shadbolt’s aerial photographs of London from a balloon or Louis Boutan’s captures of life beneath the sea, such images aren’t neutral — they shape what we think is true about the world and what we consider worth looking at.

Enjoying our latest content?

Login or create an account to continue

- Access the most recent journalism from Nature's award-winning team

- Explore the latest features & opinion covering groundbreaking research

or

Sign in or create an accountNature 645, 30-31 (2025)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-02757-7

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Felice Frankel