Revealed: the fatty cells that are the ‘bubble wrap’ of the body

Previously undescribed cells look like fat cells, but they function to provide cushioning and support in cartilage

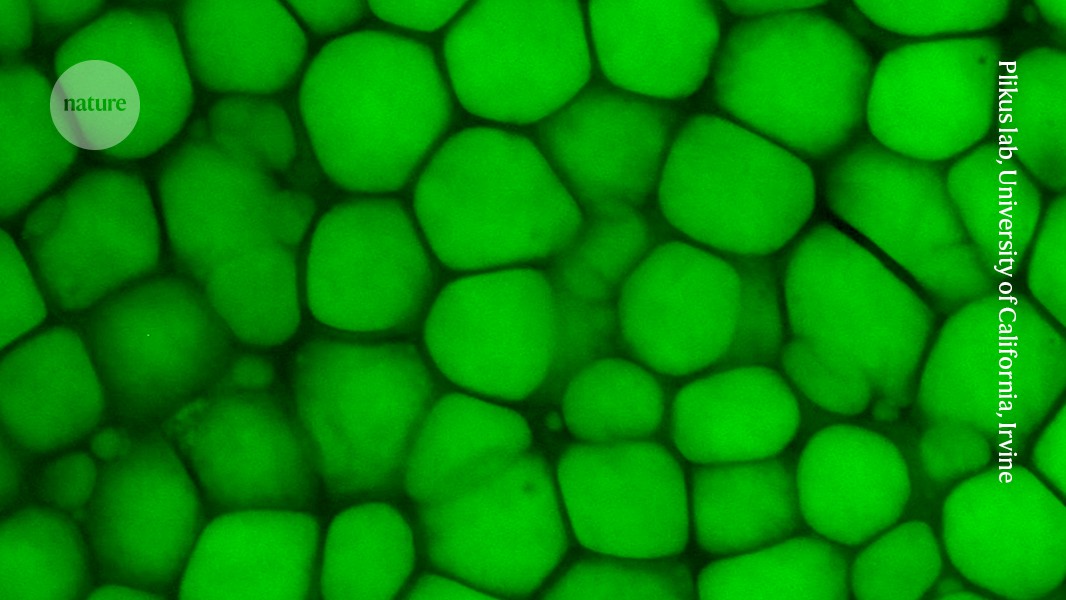

A green dye marks lipocartilage cells from the ear of a rat.Credit: Plikus lab, University of California, Irvine

The ear and the nose are squishy and stretchy thanks in part to ‘bubble wrap’ cells that provide extra cushioning and structural support to various body parts, a wide-ranging study1 shows.

These ‘lipocartilage’ cells — which are found in many mammals and have been grown from human stem cells— are fully described for the first time in a study published today in Science. The discovery of a new cell type “doesn’t happen often”, says Markéta Kaucká, an evolutionary-developmental biologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology in Plön, Germany, who wasn’t involved with the study. “This finding is really striking.”

Large but long overlooked

Lipocartilage cells have been hiding in plain sight for more than 160 years. In 1857, a German zoologist named Franz von Leydig reported that the cartilage tissue in a rat’s ear contains large cells that are filled with depots of lipids — a description that also applies to fat cells. But classic cartilage cells, called chondrocytes, are smaller than fat cells and lack a lipid depot. They churn out molecules that combine into a stiff latticework called the extracellular matrix, which provides structure and support to the cartilage tissue.

To understand the form and function of the fat-filled cells in cartilage, Maksim Plikus, a cell biologist at the University of California, Irvine, and his colleagues examined them under a microscope and analysed their biochemistry and biomechanics. The team found that these cells have enormous intracellular structures called vacuoles that are filled with lipids. As a result, under the microscope, the cells “look like iridescent pearls”, Plikus says.

But the researchers noticed that these cells don’t secrete the same signalling proteins that fat cells typically do, and that their patterns of gene activation resemble those of chondrocytes rather than those of fat cells. The most striking difference, Plikus says, was that when the researchers fed mice either a reduced-calorie or a high-fat diet, the cells remained about the same size, whereas typical fat cells would have either shrunk or ballooned in response. That suggested that lipocartilage cells don’t have a metabolic function — in contrast to fat cells, which are central to metabolism.

Instead, the large lipid reservoirs inside lipocartilage cells serve to make cartilage tissue less stiff. Chondrocytes, says Plikus, provide structure by creating an extracellular matrix akin to packing foam, which consists of a dense array of small, hard-walled voids. But lipocartilage cells are similar to bubble wrap, which uses large, air-filled pockets for cushioning.

“The idea that you regulate stiffness of tissue by controlling what’s inside the cell rather than through the extracellular matrix is new and interesting,” says Paul Janmey, a biophysicist at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia. “That’s not typically the case, even in fat tissue.”

Enjoying our latest content?

Login or create an account to continue

- Access the most recent journalism from Nature's award-winning team

- Explore the latest features & opinion covering groundbreaking research

or

Sign in or create an accountdoi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-00012-7

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Max Kozlov