AI search of Neanderthal proteins resurrects ‘extinct’ antibiotics

Scientists identify protein snippets made by extinct hominins

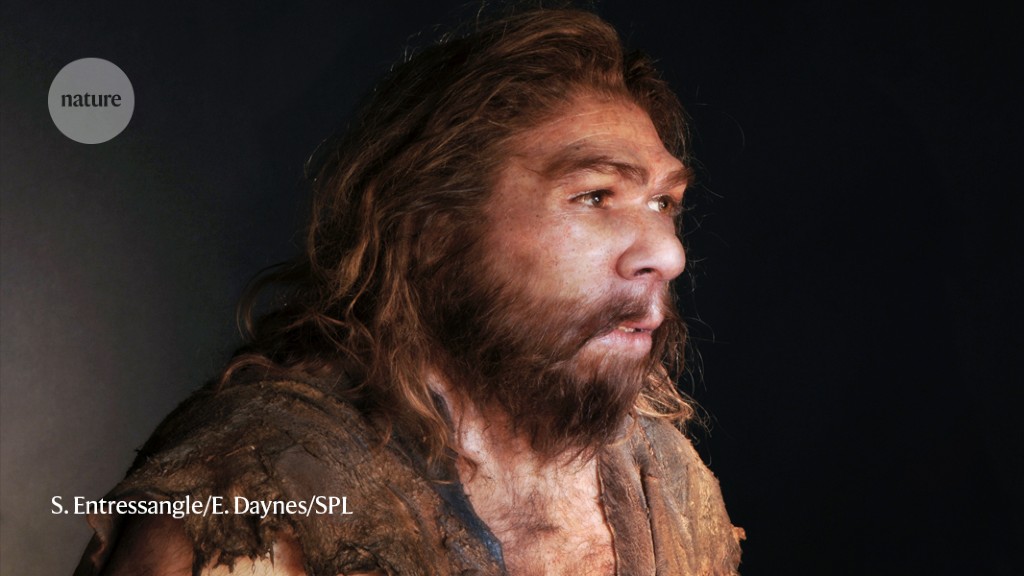

Newly identified protein snippets from Neanderthals have bacteria-fighting powers.Credit: S. Entressangle/E. Daynes/Science Photo Library

Bioengineers have used artificial intelligence (AI) to bring molecules back from the dead1.

To perform this molecular ‘de-extinction’, the researchers applied computational methods to data about proteins from both modern humans (Homo sapiens) and our long-extinct relatives, Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) and Denisovans. This allowed the authors to identify molecules that can kill disease-causing bacteria — and that could inspire new drugs to treat human infections.

“We’re motivated by the notion of bringing back molecules from the past to address problems that we have today,” says Cesar de la Fuente, a co-author of the study and a bioengineer at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. The study was published on 28 July in Cell Host & Microbe1.

Looking to the past

Antibiotic development has slowed over the past few decades, and most of the antibiotics prescribed today have been on the market for more than 30 years. Meanwhile, antibiotic-resistant bacteria are on the rise, so a new wave of treatments will soon be needed.

Many organisms produce short protein subunits called peptides that have antimicrobial properties. A handful of antimicrobial peptides, most of which were isolated from bacteria, are already in clinical use.

The proteins of extinct species could be an untapped resource for antibiotic development — a realization to which de la Fuente and his collaborators came to thanks, in part, to a classic blockbuster. “We started actually thinking about Jurassic Park,” he says. Rather than bringing dinosaurs back to life, as scientists did in the 1993 film, the team came up with a more feasible idea: “Why not bring back molecules?”

The researchers trained an AI algorithm to recognize sites on human proteins where they are known to be cut into peptides. To find new peptides, the team applied its algorithm to publicly available protein sequences — maps of the amino acids in a protein — of H. sapiens, H. neanderthalensis and Denisovans. The researchers then used the properties of previously-described antimicrobial peptides to predict which of these new peptides might kill bacteria.

Finding and testing drug candidates using AI takes a matter of weeks. In contrast, it takes three to six years using older methods to discover a single new antibiotic, de la Fuente says.

Ancient antibiotics

The researchers tested dozens of peptides to see whether they could kill bacteria in laboratory dishes. They then selected six potent peptides — four from H. sapiens, one from H. neanderthalensis and one from Denisovans — and gave them to mice infected with the bacterium Acinetobacter baumannii, a common cause of hospital-borne infections in humans.

All six peptides halted the growth of A. baumannii growing in thigh muscle, but none killed the bacteria. Five of the molecules killed bacteria growing in skin abscesses, but it took a heavy hit. The doses used were “extremely high”, says Nathanael Gray, a chemical biologist at Stanford University in California.

Tweaking the most successful molecules could create more effective versions, de la Fuente says. Likewise, altering the algorithm could improve antimicrobial-peptide identification, with fewer false positives. “Even though the algorithm that we used didn’t yield amazing molecules, I think the concept and the framework represents an entirely new avenue for thinking about drug discovery,” de la Fuente says.

“The big-picture idea is interesting,” says Gray. But until the algorithm can predict clinically relevant peptides with a higher degree of success than now, he doesn’t think that molecular de-extinction will have much of an impact on drug discovery.

Euan Ashley, a genomics and precision-health expert at Stanford University in California, is excited to see a new approach in the understudied field of antibiotic development. De la Fuente and his colleagues “persuaded me that diving into the archaic human genome was an interesting and potentially useful approach”.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02403-0

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Saima Sidik