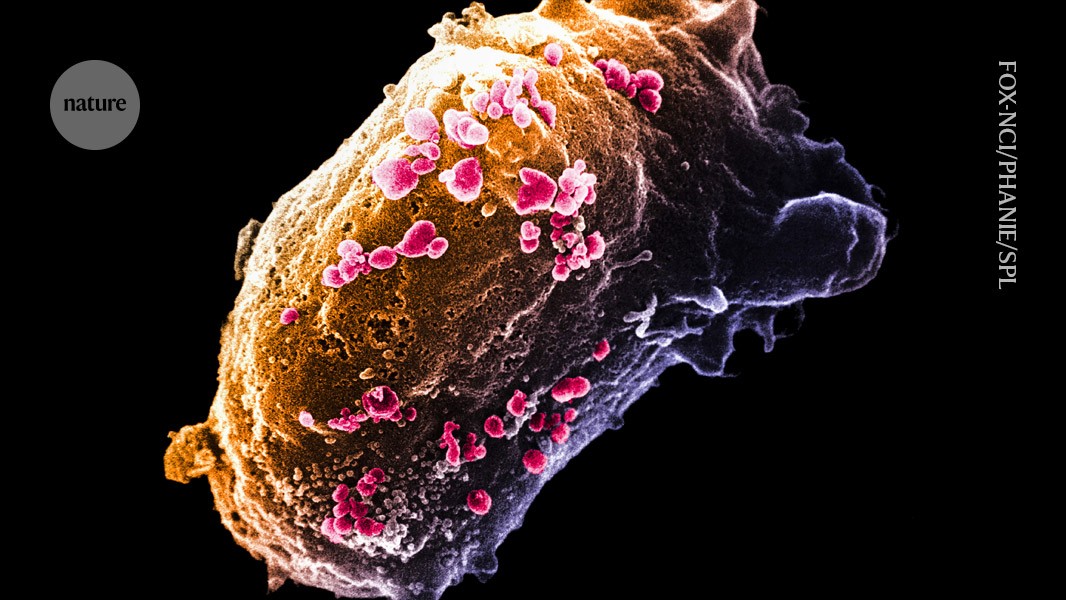

HIV: how close are we to a vaccine — or a cure?

Stem-cell transplants have freed seven people of the virus, but researchers say most long-term interventions remain a distant prospect

At a major HIV conference in July, scientists announced that a seventh person had been ‘cured’ of the disease. A 60-year-old man in Germany, after receiving a stem-cell transplant, has been free of the virus for almost six years, researchers reported.

The first such instance of eliminating HIV from a person in this way was reported in 2008. But stem-cell transplants, despite being highly effective at ridding people of the virus, are not a scalable strategy. The treatment is aggressive and poses risks, including long-term complications from graft-versus-host disease — a condition in which donor cells attack the recipient’s own tissues. The procedure was only possible in the seven successfully treated people because all of them had cancers that required a bone-marrow transplant, says Sharon Lewin, an infectious-diseases physician who heads the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity in Melbourne, Australia. “We would never even contemplate this for someone who was otherwise healthy,” Lewin says. “No one is thinking about this as a cure for HIV.”

The standard treatment for HIV is antiretroviral therapy (ART), which involves a mix of drugs, usually taken daily, that prevents the virus from replicating inside the body. ART can reduce an infected person’s viral load to an undetectable level, stopping the virus from wreaking havoc in the body and drastically reducing the risk of transmission. But, for many people, such a strategy is not enough.

Longer-term solutions are in the works. But how close are we to a cure for HIV — or a vaccine? Nature spoke with specialists to find out.

What advances have been made in the treatment of HIV?

Problems such as unreliable supply of the medicines, drug resistance and the stigma surrounding HIV infection mean that lots of people who take ART are hoping for longer-term solutions. “Many patients say they’re willing to take the risk of adverse events and even mortality risk to be cured of HIV,” says Ravindra Gupta, a microbiologist at the University of Cambridge, UK.

In most of the stem-cell-transplant cases, the cells that people received contained a mutation that prevents the expression of CCR5, a protein that the HIV virus uses to enter cells.

Although this procedure is not possible in most people with HIV, its success in a small number of patients has led to the development of gene therapies that target CCR5. There are also gene therapies in the pipeline that target the virus itself; for example, by inserting a gene that produces antibodies that keep the virus under control.

Other avenues of investigation include efforts to control or eliminate the latent HIV reservoir, which is a pool of HIV-infected cells that do not produce viral particles. These cells are thus hidden from the immune system, but they can reawaken after a person stops ART. Methods that target this latent reservoir include boosting the immune response, waking and attacking dormant HIV-infected cells or putting the virus in reservoirs permanently to sleep.

Most of these therapies have yet to make it past phase I or II in clinical trials, according to Lewin. “We’re still talking about early days.”

There have, however, been advances in longer-term treatments in the past few years. In 2020 and 2021, regulatory agencies in several countries approved a combination of injectable antiviral drugs, cabotegravir and rilpivirine, which can be given every two months to people who have HIV to keep the virus at bay. And in 2022, regulators approved the injectable lenacapavir, which is only needed every six months.

The antiviral drug lenacapavirCredit: Nardus Engelbrecht/AP via Alamy

What about preventing transmission?

In the absence of vaccines, pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, has been key to stemming the spread of HIV. Until recently, PrEP existed only in the form of oral medicines that must be taken daily to be effective. When used correctly, oral PrEP reduces the risk of contracting HIV by about 99%.

Some of the injectable antivirals approved as long-acting HIV treatments have also proved to be effective at preventing infection. In 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved cabotegravir for prophylactic use. Lenacapavir might also soon be available as a PrEP drug: in a study1 published in July, researchers reported that twice-yearly shots of lenacapavir successfully prevented HIV infection in a cohort of more than 2,000 sexually active young women and adolescent girls. In comparison, among the group who received oral PrEP, about 2% contracted the virus.

Ricardo Diaz, an infectious-diseases physician at the Federal University of São Paulo in Brazil, who is a principal investigator in a clinical trial of lenacapavir, says that there are some limitations of the injection. For example, side effects on the skin can lead some people to stop taking the drug. And its effectiveness has yet to be determined in men (a clinical trial of men is ongoing). But, given the efficacy seen in the recently published trial, lenacapavir “may be a game changer for HIV epidemics”, Diaz says.

What is happening in vaccine development?

The field has made steady progress towards a vaccine since the first HIV infection was reported in 1981 — but there’s still a long way to go, says Rama Rao Amara, an immunologist at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

One of the biggest challenges facing the field is developing a vaccine that can broadly neutralize the multiple strains of the HIV virus, Amara says. On top of that, the fact that the virus is heavily glycosylated — coated in sugar molecules — makes it difficult to design an antibody that can break through this barrier.

In a pair of papers2,3 published in Science Immunology on 30 August, researchers report an immunogen that can generate potent, broadly neutralizing antibodies against the HIV virus in macaques. These studies show that it’s possible to at least begin the process of engaging immune cells to produce broadly neutralizing antibodies, says Amara, who penned a commentary4 accompanying the papers. “That is not an easy task.” The immunogen, dubbed GT1.1, is currently being tested in a phase I clinical trial.

“HIV is not an easy virus to deal with,” Amara says. “Otherwise, we would have already had a vaccine.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-02840-5

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Diana Kwon