People’s brains aged faster during the COVID pandemic — even the uninfected

Study of nearly 1,000 people showed that brain ageing was not linked to infection status, but cognitive decline was

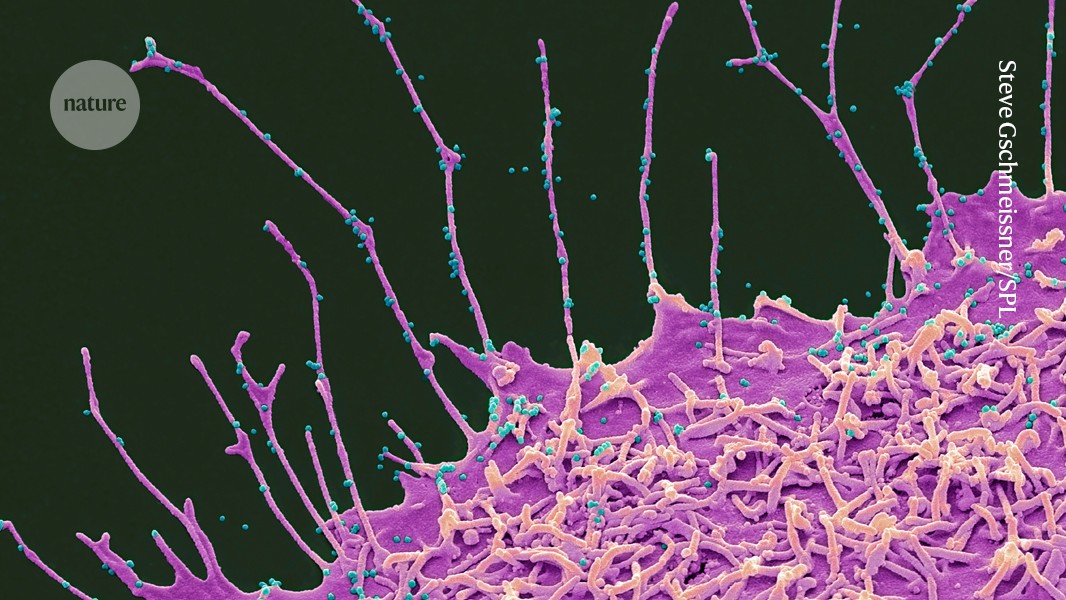

Particles of SAR-CoV-2 (blue, artificially coloured) bud from a cell (pink). Study participants who became infected with the virus lost mental flexibility.Credit: Steve Gschmeissner/SPL

The brains of healthy people aged faster during the COVID-19 pandemic than did the brains of people analysed before the pandemic began, a study of almost 1,000 people suggests1. The accelerated ageing occurred even in people who didn’t become infected.

The accelerated ageing, recorded as structural changes seen in brain scans, was most noticeable in older people, male participants and those from disadvantaged backgrounds. But cognitive tests revealed that mental agility declined only in participants who picked up a case of COVID-19, suggesting that faster brain ageing doesn’t necessarily translate into impaired thinking and memory.

The study “really underlines how significant the pandemic environment was for mental and neurological health”, says Mahdi Moqri, a computational biologist who studies ageing at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts. It’s unclear whether the pandemic-associated brain ageing is reversible, because the study analysed scans taken at only two time points, adds Moqri.

The findings were published today in Nature Communications.

Pandemic effect

Previous research has offered clues that SARS-CoV-2 infections can worsen neurodegeneration and cognitive decline in older people. But few studies have explored whether the pandemic period — a tumultuous time marked by social isolation, lifestyle disruptions and stress for many — also affected brain ageing, says study co-author Ali-Reza Mohammadi-Nejad, a neuroimaging researcher at the University of Nottingham, UK.

To find out, Mohammadi-Nejad and his colleagues analysed brain scans collected from 15,334 healthy adults with an average age of 63 years in the UK Biobank (UKBB) study, a long-term biomedical monitoring scheme. They trained machine-learning models on hundreds of structural features of the participants’ brains, which taught the model how the brain looks at various ages. The team could then use these models to predict the age of a person’s brain. The difference between that value and a participant’s chronological age is the ‘brain age gap’.

The team then applied the brain-age models to a separate group of 996 healthy UKBB participants who had all had two brain scans at least a couple of years apart. Some of the participants had had one scan before the pandemic and another after the pandemic’s onset. Those who’d had both scans before the pandemic were designated the control group. The models estimated each participant’s brain age at the time of both scans.

Nearly six months more

The models predicted that the brains of people who had lived through the pandemic had aged 5.5 months faster on average than had those of people in the control group, irrespective of whether those scanned during the pandemic had ever contracted COVID-19. “Brain health is shaped not only by illness, but by our everyday environment,” says Mohammadi-Nejad.

Login or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

Sign in or create an accountdoi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-02313-3

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Gemma Conroy