Why is landing safely on the Moon so hard?

The failure of the ispace lunar lander highlights the challenges, in particular for nascent private companies

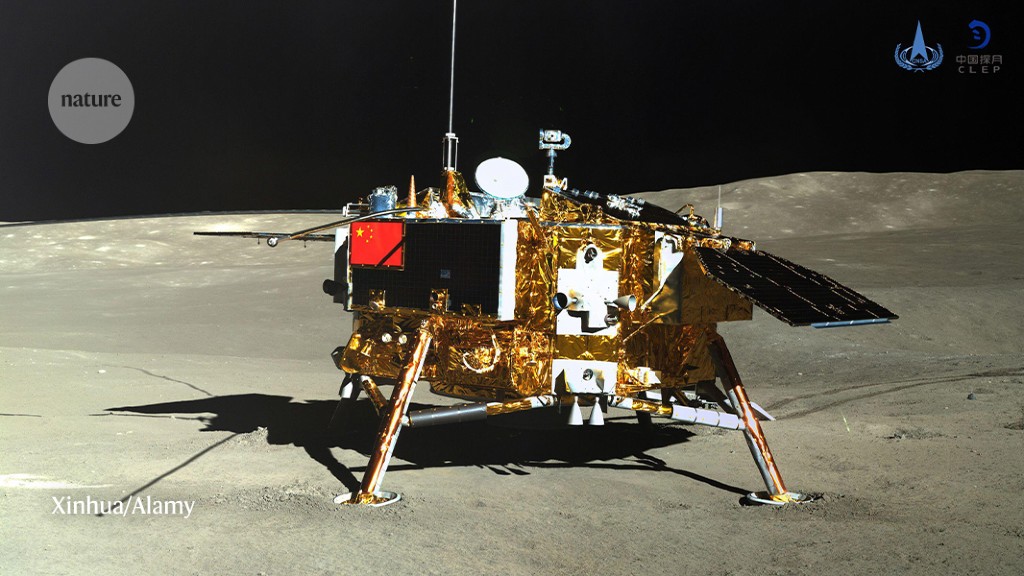

China's Chang'e-4 mission made the first-ever landing on the far side of the Moon in 2019.Credit: Xinhua/Alamy

The M1 spacecraft, built by Tokyo-based company ispace, made a valiant bid to become the first private space vehicle to land on Moon. Instead, on 25 April, it became the latest in a long line of Moon missions that didn’t quite make it, apparently crashing on the lunar surface. Why is it so hard to touch down safely on the Moon? And when might the first private company succeed?

Only three entities have successfully soft-landed on the Moon — the government-funded space agencies of China, the Soviet Union and the United States. And only China has done it since the 1970s and on its first attempt.

“What makes landing on the Moon so difficult is the number of variables to consider,” says Stephen Indyk, director of space systems at Honeybee Robotics in Greenbelt, Maryland. Compared with Earth, for example, the Moon has reduced gravity, very little atmosphere and lots of dust.

To pull off a successful landing, engineers need to anticipate how a spacecraft will interact with this environment — and spend money testing how things might go wrong. “Tests, tests and more tests are needed to prove out the landing system in as many scenarios as possible,” Indyk says. “And even then, nothing is guaranteed.”

Spectacular failures

ispace is only the second private company to try to land on the Moon. In 2019, an attempt by the Israeli company SpaceIL ended in a crash-landing as well.

It’s no surprise that commercial companies are running into challenges in their bids to land on the Moon, Indyk says. In the 1960s, when the United States and the Soviet Union were racing to land there, they crashed spacecraft after spacecraft before each finally succeeded in 1966.

The government space agencies were able to learn from each landing attempt. Today, by contrast, private companies are expected to repeat these successes, without government resources and without lessons gleaned from many failed and successful missions, Indyk says. “That’s a lot to ask of a private enterprise to get it right on the first attempt.”

In 2013, China landed successfully on the Moon on its first try with its Chang’e 3 mission. China also accomplished the first-ever landing on the far side of the Moon, and brought back samples of Moon rocks. But India, for its part, crashed during its attempt to land on the Moon in 2019; it will try again later this year.

Early challenges

Getting a mission to the Moon, around 384,000 kilometres from Earth, is much more challenging than lofting a satellite into low-Earth orbit — and failures can occur early on, even for missions that don't plan to land. This happened with NASA’s Lunar Flashlight mission, a small spacecraft that launched in December and was supposed to map the Moon’s ice. Its propulsion system malfunctioned soon after launch and may keep it from reaching an orbit from which it can do the intended science.

Even if a lander makes it to the vicinity of the Moon, it still has to navigate its way down to the surface with no global-positioning satellites for guidance and virtually no atmosphere to help to slow it down. Once it gets within the crucial last few kilometres, its software has to deal quickly and autonomously with any last-minute challenges, such as its sensors potentially becoming confused by large amounts of dust kicked up from the surface by exhaust plumes.

Both of the 2019 landing failures probably stemmed from software and sensor issues during these final moments. And early indications suggest that this week’s ispace failure could have been caused by the lander running out of propellant just before it touched down.

Commercial Moon rush

The ispace crash raises the bar for a flurry of other commercial missions scheduled to land on the Moon, including as many as three by the end of the year that are partially funded by NASA. Those landers are part of the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) programme, in which private companies aim to build landers and fly payloads from NASA and other customers to the lunar surface.

One of these landers, built by the company Astrobotic in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was anticipated to take off in early May, but delays in readying its rocket means the launch will probably slide by several months at least. That could mean that a lunar lander from Intuitive Machines, in Houston, Texas, is first up to launch, perhaps as early as June.

These companies will be looking at the experience of others as they try to achieve the first successful private Moon landing. “The rising tide lifts all boats,” said Alan Campbell, an engineer who works on CLPS projects at the company Draper in Cambridge, Massachusetts, at a lunar conference this week before the ispace failure. “If we can learn from what happens for commercial or NASA CLPS missions and apply that across — that’s absolutely something we should be doing.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-01454-7

This story originally appeared on: Nature - Author:Witze, Alexandra